Arbitrator diversity at the Court of Arbitration for Sport - Part One

‘Pale, male, and stale’ is a phrase which has been used to criticise a lack of arbitrator diversity in international arbitration – alluding to the frequency with which disputes are determined by old, white, men.

The Court of Arbitration for Sport (“CAS”) has been similarly criticised for the lack of diversity in the arbitrators appointed to hear disputes, with one former CAS arbitrator concluding that “the CAS retains the characteristics of the oldest network in sport – the old boys’ club”.

This article is the first in a two-part series following an extensive research project by Morgan Sports Law, in which the data from publicly available CAS cases was extracted and reviewed to examine how diverse appointed CAS arbitrators are, in terms of their gender and ethnicity (by reference to skin colour).

In this Part One, that data is analysed and reported. Part Two will then discuss why arbitrator diversity is so important, and how the CAS’s diversity problem might be resolved.

The data

This article presents data from 2,081 CAS awards issued between January 2000 to September 2020 and published on the CAS Jurisprudence webpage. For the purposes of this article’s statistics, where multiple unique case numbers have been assigned to a matter (e.g. where appeals have been heard together), it has been recorded as multiple cases (and thus as multiple appointments for each arbitrator involved).

Where possible, arbitrator details were taken from the CAS List of Arbitrators webpage, with outstanding information taken from other reliable webpages.

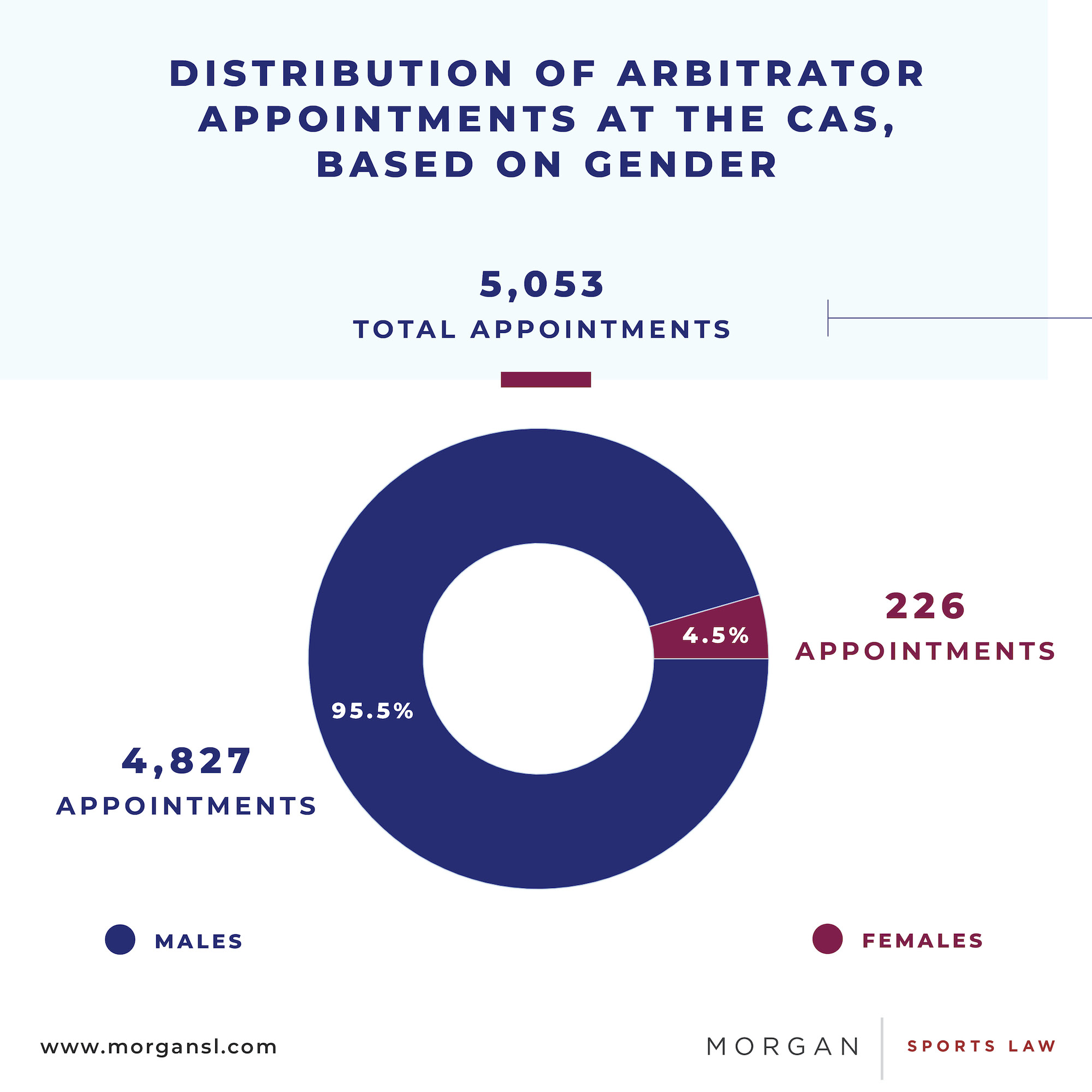

Overall, the 2,081 awards capture 5,053 arbitrator appointments spread between 330 arbitrators. That appointments total is made up of 586 sole arbitrator appointments and 4,467 appointments to a three-arbitrator panel.

Overall diversity

Reviewing the characteristics of the 330 arbitrators identifies serious diversity issues as regards both gender and ethnicity (by reference to skin colour).

As to gender, only 38 of the 330 unique arbitrators are female (11.5%) with these arbitrators receiving only 226 appointments (4.5%) between them. Each female arbitrator receives on average more than 10 fewer appointments than their male counterparts (6 appointments per female arbitrator versus over 16 appointments per male arbitrator).

That analysis is skewed by a small number of male arbitrators who have been appointed in a disproportionately large number of procedures. However, even if one removes from the analysis any arbitrator who has been appointed over 100 times (a group made up of 14 men) the remaining male arbitrators still receive, on average, almost twice as many appointments as female arbitrators (10.5 versus 6). Accordingly, it is clear that the gender imbalance is not explained by the popularity of this small group of male ‘super-arbitrators’.

A similar analysis regarding the appointed arbitrators’ ethnicity (by reference to skin colour) reveals that just 17.3% of the 330 arbitrators are non-white and just 3.6% are black (57 and 12 arbitrators, respectively). However, further analysis reveals an even direr picture: non-white arbitrators received only 7.9% of the appointments in the 2,081 cases studied, whilst black arbitrators received only 0.8% of the appointments.

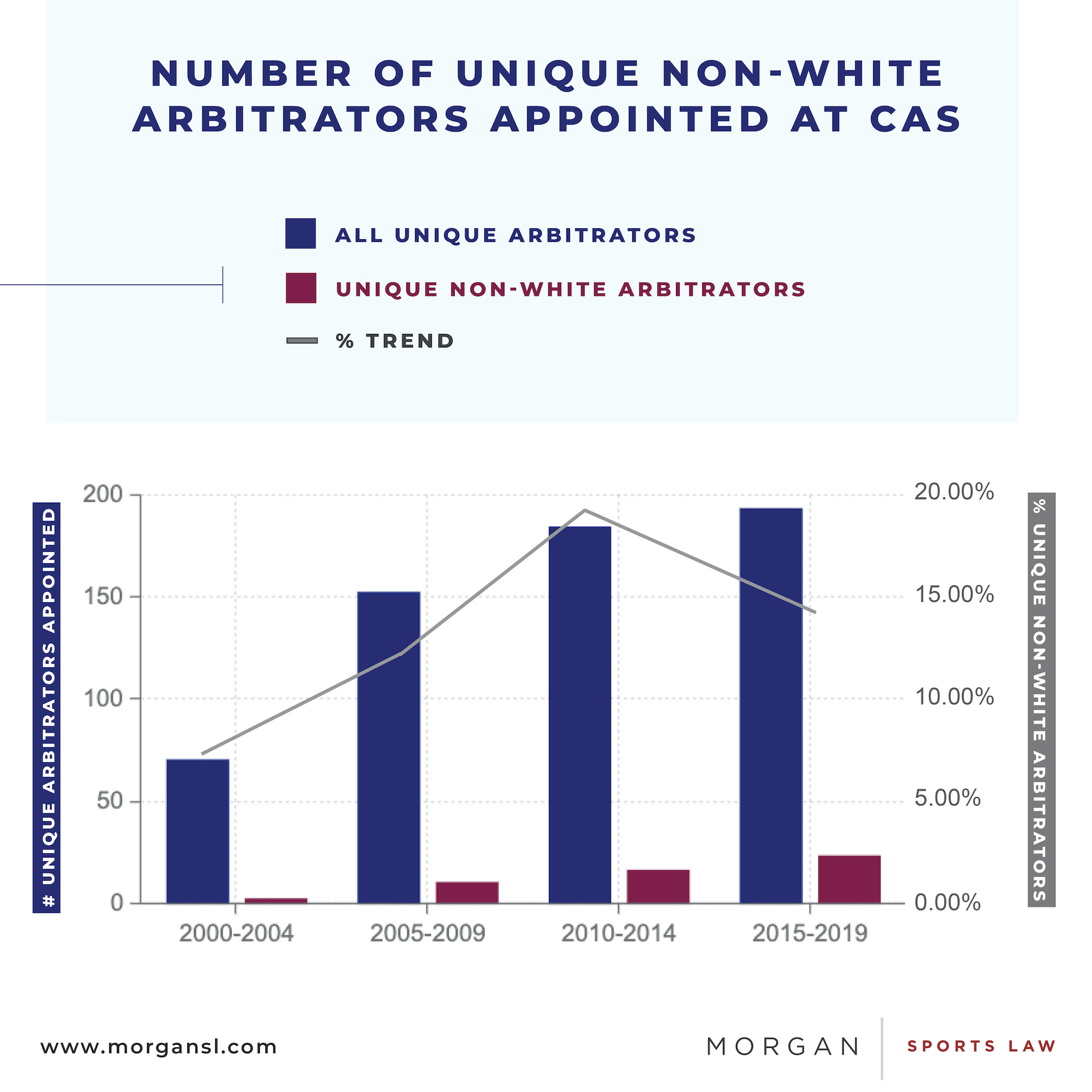

That notwithstanding, diversity as regards both gender and ethnicity (by reference to skin colour) has improved since 2000, as determined by comparing the data from four discrete five-year periods (2000-2004, 2005-2009, etc.).

In the period 2000-2004 4.2% of the unique arbitrators appointed were female. In comparison, in 2015-2019 12.4% of the unique arbitrators appointed were female. Thus, a significant improvement occurred in that regard. However, the picture is less positive when one considers the percentage of total appointments received by female arbitrators, which only rose from 3.4% to 4.9% when comparing those periods.

A comparison of these statistics to the arbitrator gender diversity at other international arbitral tribunals demonstrates that the CAS still has some way to go simply to meet the (underwhelming) standards being set elsewhere. For example:

- the ICC’s Dispute Resolution 2019 Statistics record that 21% of appointments were to female arbitrators; and

- Gaillard et al.’s 2020 analysis of pending ICSID arbitrations noted that 16% of appointments were to female arbitrators.

As regards ethnicity (again, by reference to skin colour), the number of unique non-white arbitrators and unique black arbitrators appointed increased, with an almost five-fold increase in non-white arbitrators and eight-fold increase in black arbitrators between 2000-2004 and 2015-2019 (during which time case numbers rose by a factor of approximately 2.5). However, a concerning pattern is revealed when 2010-2014 and 2015-2019 are compared, as the percentage of non-white and black unique arbitrator appointments decreased.

Despite this, the percentages of all appointments which went to non-white and black arbitrators both increased when comparing 2010-2014 to 2015-2019, meaning that each non-white / black arbitrator appointed in 2015-2019 received a greater number of appointments than in 2010-2014 (increasing from an average of 3.6 to 5.8 decisions per non-white arbitrator and from 2 to 2.5 decisions per black arbitrator).

Therefore, one can conclude that arbitrator diversity at the CAS has improved slightly since 2000, although not at as great a rate as it could have, and nowhere near enough to reflect the diversity of its user base.

Diversity in appointments by the CAS

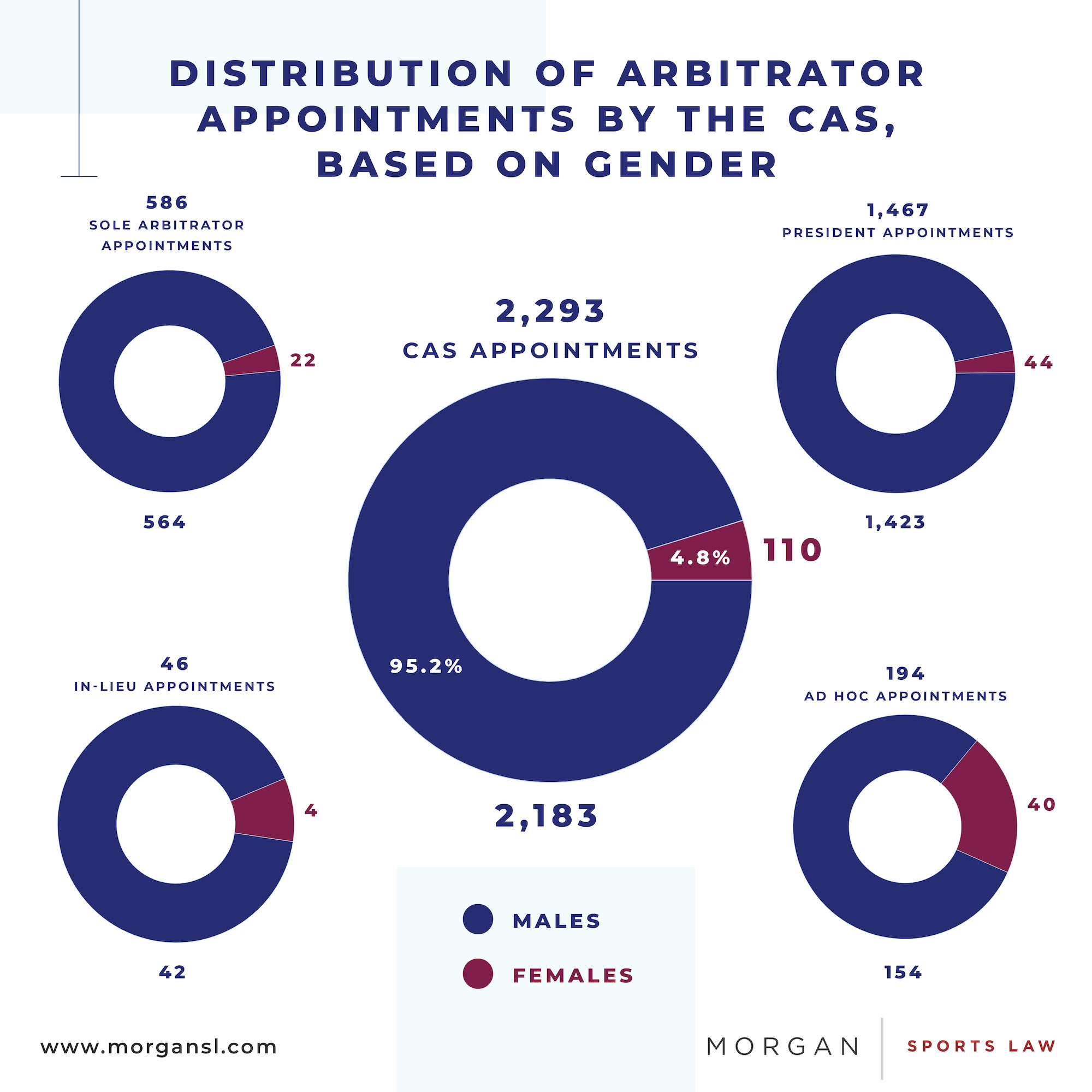

Wing members of a panel are typically nominated by the parties. However, the CAS has responsibility for appointing sole arbitrators, certain panel presidents, wing members appointed in lieu of a party’s nomination, and arbitrators in ad hoc procedures.

In this regard, it is notable that the CAS would appear to have greater responsibility for arbitrator appointments than other arbitral tribunals. Indeed, of the 5,063 appointments considered here, 45% fall into one of these “CAS-controlled” categories, whereas the ICC’s Dispute Resolution 2019 Statistics record that only 27% of arbitrator appointments were made by the ICC itself.

The CAS is intended to serve the world of sport and its incredibly diverse constituents. It is not unreasonable for those constituents to expect the arbitrator list and the panels composed of arbitrators from that list to reflect similar diversity. Given that CAS controls around 45% of the appointments, it is clear that it can significantly improve the diversity of panels even if parties do not take steps to do so.

Moreover, whilst parties will have tactical reasons for choosing certain arbitrators (a point that will be addressed further in Part Two), the CAS does not have any stake in the outcome of cases, and thus can, and many would contend should, actively take steps to increase the diversity of appointed arbitrators.

However, as regards the studied cases, the data reveals that:

- only 4.8% of CAS-controlled appointments were to female arbitrators;

- only 6.2% of CAS-controlled appointments were to non-white arbitrators; and

- only 1% of CAS-controlled appointments were to black arbitrators.

Disappointingly, those statistics are broadly in line with the overall percentages of appointments received (i.e. including party nominated arbitrators), as set out above, and show a similar pattern of (modest) improvement when considering how they have changed over time. Accordingly, the available data indicates that – on the face of it – the CAS is not making a particular effort to improve diversity as regards arbitrators appointed by it.

Moreover, the CAS’s record of appointing female and/or non-white arbitrators as sole arbitrators or panel presidents is particularly poor. Indeed, as regards the cases studied, the CAS only appointed a female and/or non-white arbitrator as sole arbitrator or panel president in 3.2% of cases.

Thus, it is apparent that, in appointing arbitrators, CAS could and should be doing more to ensure arbitrator diversity.

Diversity in appointments by sports institutions

In addition to the CAS, sports institutions which repeatedly appear in CAS proceedings can also play a significant part in improving arbitrator diversity. Indeed, many sports institutions have committed to diversity and/or committed themselves, by their statutes, to equality (see for example Article 2(g) of the UCI’s Constitution which lists an objective of promoting “gender parity and equity in all aspects of cycling”).

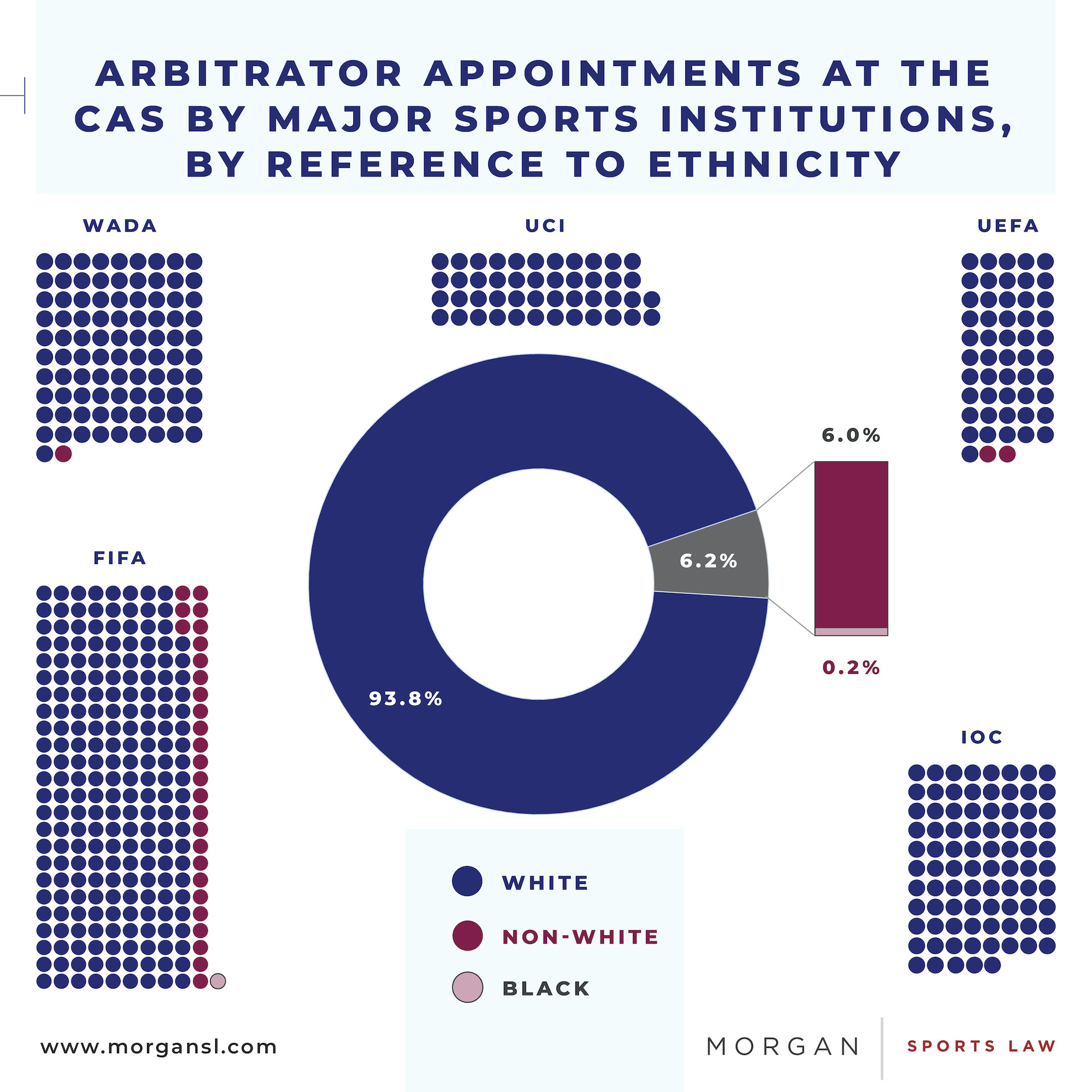

According to research by Professor Johan Lindholm, the five sports institutions involved in CAS proceedings most frequently are: WADA, FIFA, the IOC, the UCI, and UEFA. Unfortunately, a review of the appointments made by those five institutions across the studied cases reveals a dire state of affairs.

Collectively, the five institutions have been responsible for 517 different arbitrator appointments. Only 17 (i.e. 3.3%) of those appointments were of female arbitrators, with 16 of those appointments having been made by either WADA or FIFA. Twelve of those appointments related to the same female arbitrator. In fact, the 17 appointments were spread across just four different female arbitrators.

In their collective 184 appointments across the studied cases, the IOC, the UCI, and UEFA only once appointed a female arbitrator (that being a UEFA appointment).

Analysis of those 517 appointments as regards ethnic diversity (by reference to skin colour) also reveals disturbing results. Only 31 appointments (i.e. 6%) were of non-white arbitrators, and only one appointment was of a black arbitrator (i.e. 0.2%). Indeed, across the cases examined, the IOC and the UCI did not appoint a single non-white arbitrator (despite making 131 arbitrator appointments between them).

These shocking statistics point to a significant opportunity for improvement. However, an analysis of how these statistics have changed over time suggests that this opportunity is not being taken – as there was in fact a decrease in the percentage of appointments given to non-white arbitrators by these five sports institutions in 2015-2019, as compared to 2010-2014.

Conclusion

It is clear from the above analysis that, whilst diversity in arbitrator appointments has (for the most part) increased over the last 20 years, there is still a very long way to go. Moreover, the current rate of progress is far too slow.

The question might be asked as to whether the lack of diversity in sports arbitration matters? If a CAS panel is made up of three renowned and experienced lawyers, does it matter that they are all white and male? Part 2 in this series will explain why diversity at CAS does matter and, accordingly, will provide suggestions as to how this state of affairs could be improved to ensure that CAS arbitrations move away from being an “old boys’ club”.

Footnote

1. To use the term introduced by Lindholm, J. (Ed.) The Court of Arbitration for Sport and Its Jurisprudence., T.M.C. Asser Press, 1.

2. The CAS is responsible for the selection of panel presidents in appeal procedures. In ordinary (i.e. non-appeal) procedures the party nominated arbitrators decide on the identity of the panel president, although the CAS will select the panel president if the party nominated arbitrators are unable to agree on a president within a set timeframe.

3. Under the rules of the CAS Ordinary Division, if the parties have opted for a three-arbitrator panel, the two party-nominated arbitrators will select the panel chair. If the co-arbitrators cannot agree on the identity of the chair, then the President of the Ordinary Division will appoint the chair. In appeal proceedings (where the CAS acts as an appellate tribunal), the panel chair (known as the panel president) is always selected by the CAS itself (specifically, by the President of the Appeals Division). In both ordinary and appeal proceedings, if a respondent fails to nominate an arbitrator within the set time limits, the President of the relevant CAS division will make the appointment in lieu of the party. Finally, the CAS itself appoints all of the arbitrators hearing its ad hoc proceedings. Together, these factors explain why the CAS is responsible for a higher proportion of arbitrator appointments than other arbitral tribunals.

4. That data deriving from the available published cases.

5. Notably, the list of CAS arbitrators is more diverse than the arbitrators in fact appointed by the CAS. Thus, it is not the case that the CAS is hamstrung by the arbitrator list.

6. Lindholm, J. (2019) CAS from the Litigants’ Perspective. In: Lindholm, J. (Ed.) The Court of Arbitration for Sport and Its Jurisprudence., T.M.C. Asser Press, 1. 287 – 312.