The CAS: Explained

1. INTRODUCTION

“A kind of Hague Court in the sports world”. With those words, the former president of the International Olympic Committee (the “IOC”), Juan Antonio Samaranch, introduced the concept of the Court of Arbitration for Sport (the “CAS”), in 1982.

The establishment of the CAS was motivated by the need to create a specialised and dedicated tribunal which would resolve all sports-related disputes in a flexible and efficient manner. It has also been reported that Taiwan’s decision in 1979 to file lawsuits against the IOC in the Swiss courts played a role in the IOC’s decision to establish the CAS.

Following ratification of the CAS statutes by the IOC on 30 June 1984, the CAS came into existence, and began to operate from its headquarters in Lausanne, Switzerland.

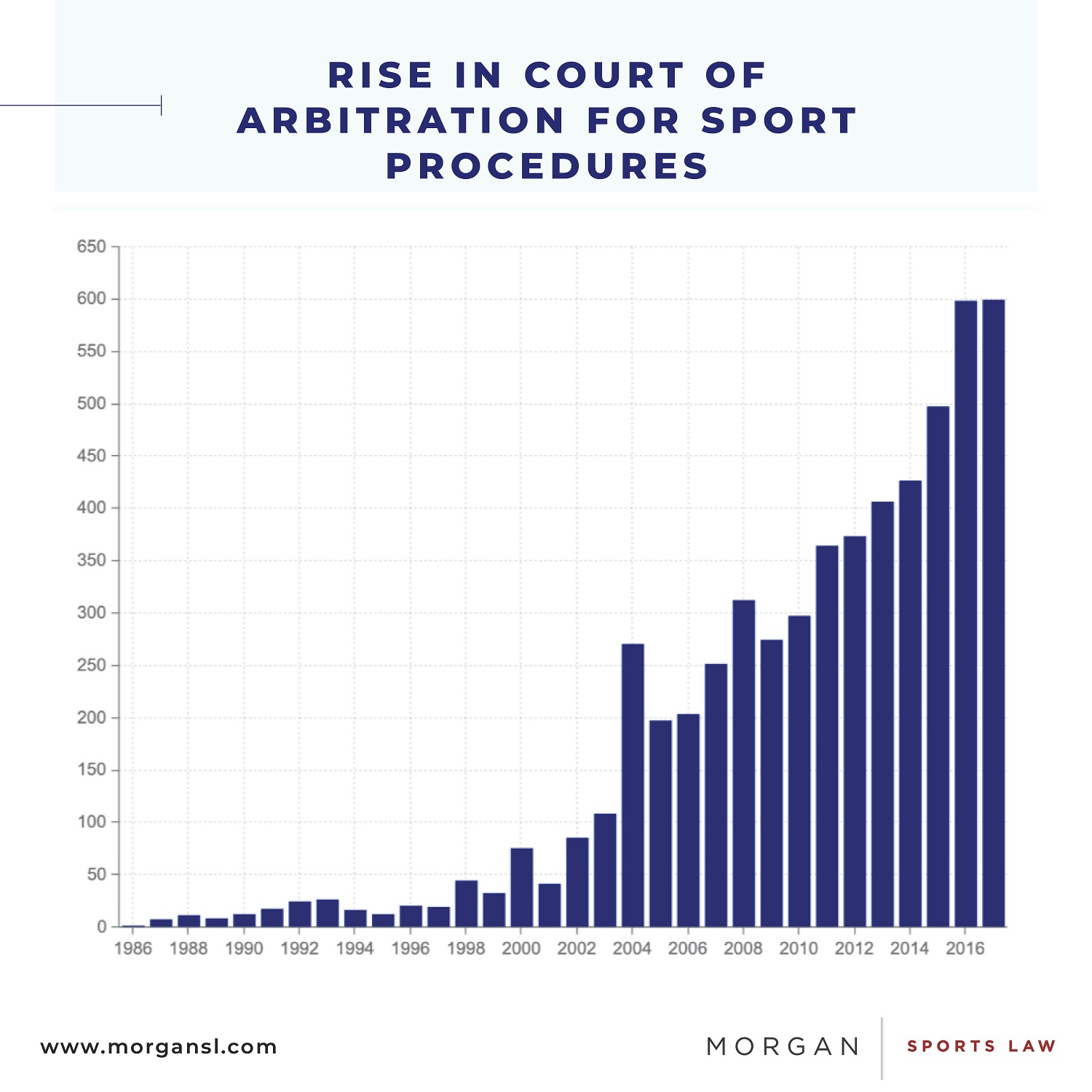

Despite high expectations, the CAS initially developed very slowly, rendering on average only three decisions per year during its first 10 years of existence. However, the CAS is now well established as the “supreme court” for sports disputes and handles around 600 arbitrations per year.

2. STRUCTURE

The CAS is a private arbitral institution. Its objective is to resolve sports-related disputes through arbitration and mediation. The organisation of the CAS, and the procedures brought before it, are governed by the Code of Sports-related Arbitration (the “CAS Code”), the latest version of which came into force on 1 July 2020.

The CAS is managed and administered through a Swiss foundation called the International Council of Arbitration for Sport (“ICAS”). ICAS was created as part of a deep structural transformation of the CAS following the decision of the Swiss Federal Tribunal in the Gundel case in 1993.

One of the most notable particularities of the CAS system is that the seat of every arbitration is Lausanne, Switzerland. As such, the Swiss lex arbitrii always applies. That means that a CAS award can (initially at least) only be challenged before the Swiss Federal Tribunal and only on very narrow grounds.

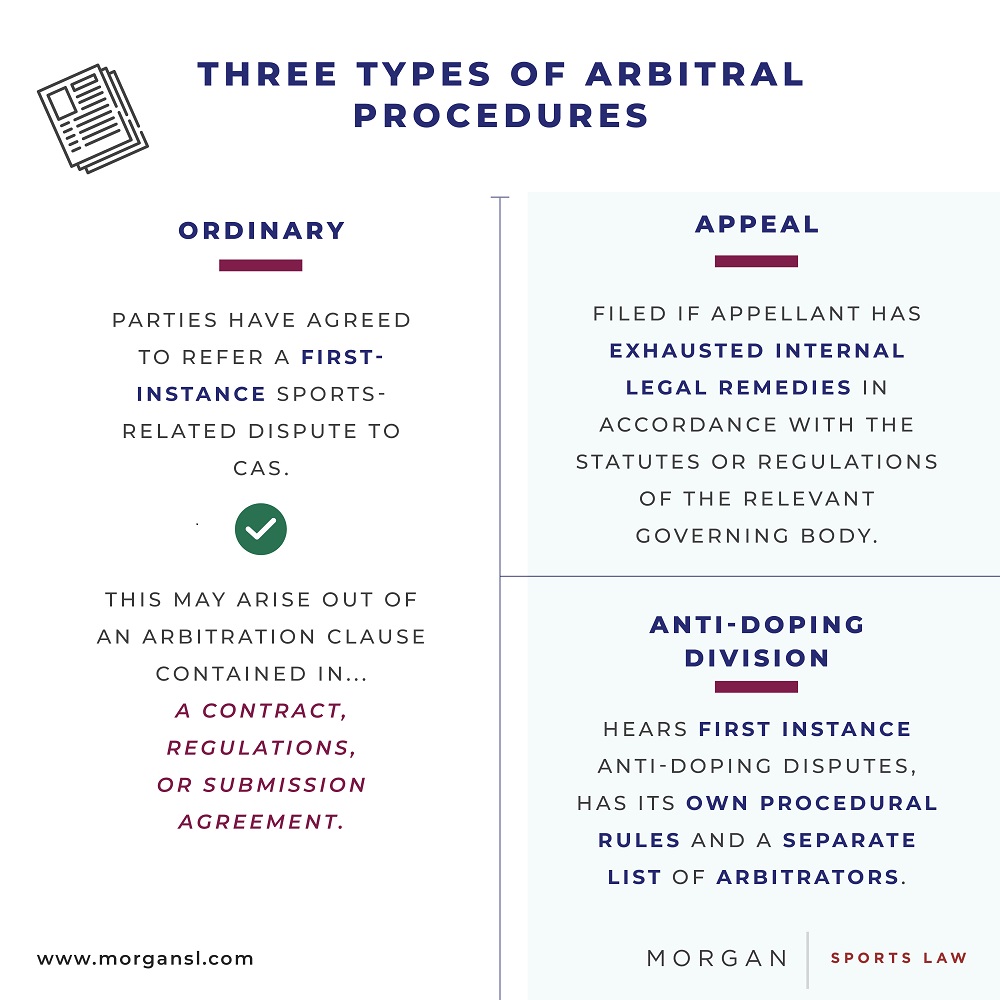

The CAS administers three types of arbitral procedures: ordinary procedures, appeal procedures and, since January 2019, first instance anti-doping disputes heard by the Anti-Doping Division (“ADD”).

An ordinary procedure is started whenever the parties have agreed to refer a first-instance sports-related dispute to CAS. Such agreement may arise out of an arbitration clause contained in a contract or regulations, or by means of a submission agreement.

On the other hand, an appeal against the decision of a federation, association or sports-related body may be filed with CAS if the statutes or regulations of that body so provide or if the parties have concluded a specific arbitration agreement, and if the appellant has exhausted the legal remedies available to it prior to the appeal, in accordance with the statutes or regulations of that body.

The newly formed ADD is a first-instance tribunal that exclusively hears anti-doping disputes. Proceedings are commenced where an international federation or other results management authority has delegated its powers to decide first instance anti-doping cases to the ADD. The ADD has specific procedural rules and a separate list of arbitrators.

3. ARBITRAL TRIBUNALS

The CAS determines disputes through three-member panels or through a sole arbitrator, with the assistance of the CAS Court Office. Another characteristic of the CAS arbitration system is that, unlike many other arbitral institutions, parties must choose an arbitrator from the published list of CAS arbitrators, currently composed of 392 arbitrators from 107 different nationalities.

The CAS arbitrators are appointed for a term (which may be renewed) of four years by the ICAS, on the proposal of the IOC, the International Federations and the National Olympic Committees and by their respective athlete commissions. CAS arbitrators must possess:

“appropriate legal training, recognized competence with regard to sports law and/or international arbitration, a good knowledge of sport in general and a good command of at least one CAS working language".

4. TYPES OF DISPUTES

In principle, two types of disputes may be submitted to the CAS: commercial disputes and regulatory disputes.

Commercial disputes typically cover issues relating to the validity, execution and termination of contracts. For instance:

(a) Sponsorship agreements;

(b) Broadcasting agreements;

(c) Agreements relating to the organisation of sporting events;

(d) Agreements relating to the transfers of players; and

(e) Employment contracts.

A broad range of regulatory disputes are heard by the CAS, from anti-doping and disciplinary matters to eligibility and selection disputes.

In terms of sports, football is by far the highest represented sport before the CAS. As of today, there are 1,076 published decisions related to football, which was almost seven times as much as the second ranked sport, athletics. In fact, the study found that CAS has published decisions in 68 different sports, and that the number of football decisions is greater than the total number of decisions relating to the other 67 sports.

5. CONCLUSION

We hope that this article provides a useful introduction to the CAS.

In our next article, we will explore in further detail the process by which procedures (both ordinary and appeal) are initiated before the CAS. Keep an eye on our website for details in due course.

Authored By

Lisa Jones

Associate

Footnote

1. See Mathieu Reeb, 'Le Tribunal Arbitral du Sport son histoire et son fonctionnement', Digest of CAS Awards III 2001-2003, Volume 3 (2004) p. xvii.

2. See Shuli Guo, China and the Court of Arbitration for Sport, Marquette Spots Law Review, Vol. 25, issue 1, p. 301. It has been suggested that Juan Antonio Samaranch was concerned that an ordinary court could pass decisions which would directly influence the world of sport.

3. See Guo supra

4. See Johan Lindholm, The Court of Arbitration for Sport and its Jurisprudence, Springer (1st edition) p. 4

5. Similar to, for instance, the London Court of International Arbitration (LCIA) and the International Court of Arbitration of the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC).

6. For a detailed explanation of how the ICAS is organised and structured see Arts. S1 to S11 of the CAS Code.

7. In 1992, Elmar Gundel appealed before the CAS a decision of the Fédération Equestre Internationale that had suspended Mr Gundel due to an anti-doping rule violation. The CAS rendered an award partially upholding the appeal (the suspension was reduced from three months to one month). Dissatisfied with the CAS award, Mr Gundel initiated proceedings before the Swiss Federal Tribunal to set aside the CAS award. The Swiss Federal Tribunal confirmed that the CAS was a valid arbitral tribunal, but raised some concerns as regards the independence of the CAS vis-à-vis the International Olympic Committee.

8. See Ulrich Haas, Applicable law in football-related disputes - The relationship between the CAS Code, the FIFA Statutes and the agreement of the parties on the application of national law, CAS Bulletin 2015/2 p. 8

9. Those listed at Article 190 of the Swiss Private International Law Act (“PILA”). The above notwithstanding, after the proceedings before the Swiss Federal Tribunal, parties may still try to seek extraordinary recourse before the European Court of Human Rights (“ECHR”) (See., for instance, ECHR judgement of 2 October 2018 in the matter Mutu and Pechetein v. Switzerland). Notably, the ECHR found that Switzerland was capable of being sued under the ECHR because it upheld the CAS decisions, which were alleged to have violated Mr Mutu’s and Ms Pechstein’s human rights.

10. See Article R27 of the CAS Code.

11. The CAS website provides for the following standard clause: "Any dispute arising from or related to the present contract will be submitted exclusively to the Court of Arbitration for Sport in Lausanne, Switzerland, and resolved definitively in accordance with the Code of sports-related arbitration."

12. Article R47 of the CAS Code. The statutes or regulations of the body which issued the decision must expressly provide for the jurisdiction of the CAS.

13. Article A1 of the Arbitration Rules – CAS ADD.

14. See Article S14 of the CAS code.

15. The majority of arbitrations before the CAS qualify as an international arbitration pursuant to PILA (because, at the time of the conclusion of the arbitration agreement, at least one of the parties had neither its domicile nor its habitual residence in Switzerland). As such – and given that all CAS arbitrations are seated in Lausanne, Switzerland – the arbitrability of a dispute should always be analysed under the basis of Article 177 PILA which provides that a dispute is arbitrable as long as it has a financial interest.

16. With thanks to Mario Flores Chemor (former Morgan Sports Law Associate) for his contribution to this article.