Compensation payable by footballers for breach of contract

1. INTRODUCTION

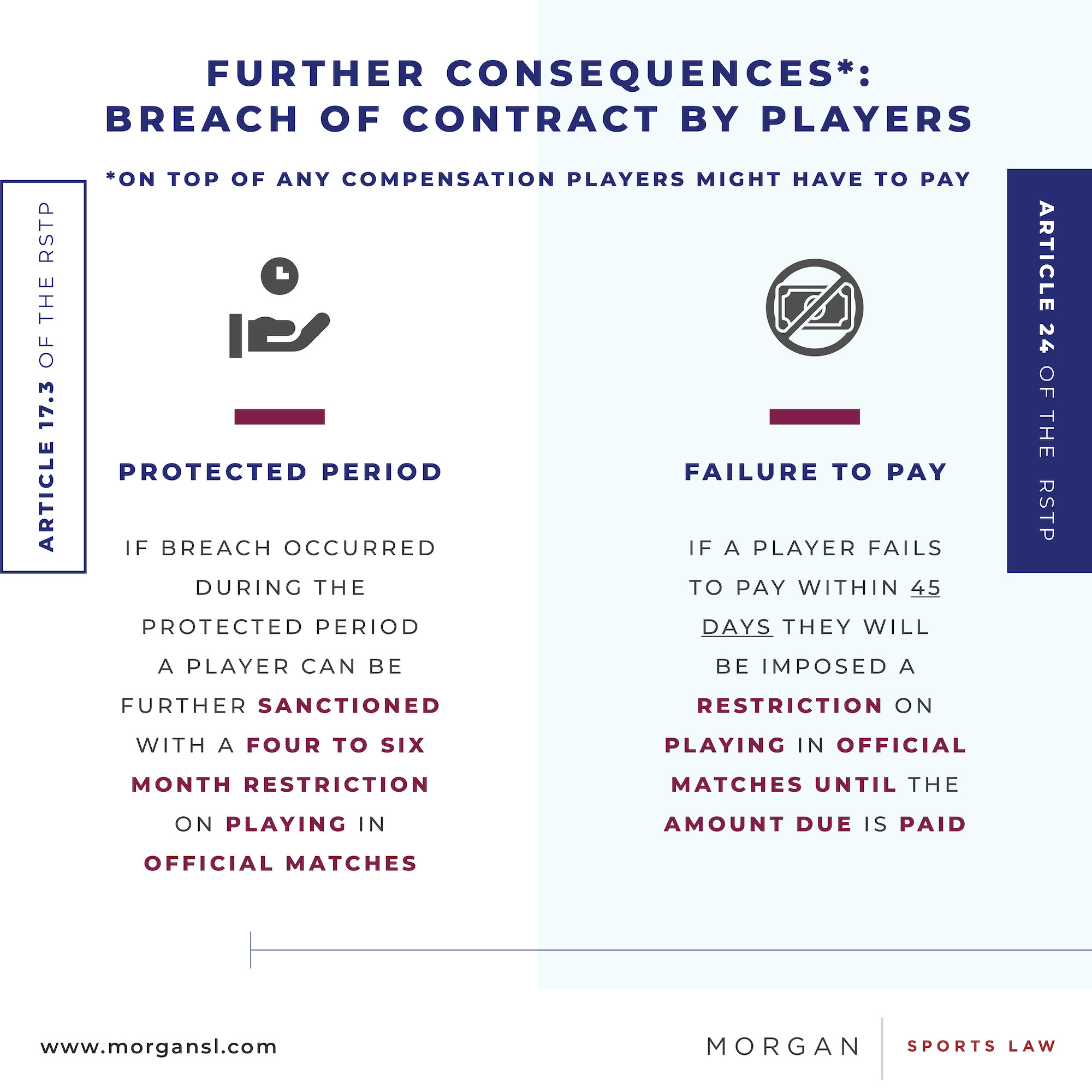

Article 17 of FIFA’s June 2018 edition of the Regulations on the Status and Transfer of Players (the “RSTP”) provides clear guidance to calculate compensation owed to a player in the event of a breach of contract by a club, by express reference to the residual value of said contract.

However, the same cannot be said about compensation owed to a club in the event of a breach by a player. This lack of certainty is obviously undesirable from the perspective of both players and clubs.

Prior to June 2018, the RSTP provided for a generic approach to compensation for breach of contract, in respect of both players and clubs. Such an approach left a wide margin of discretion for the judges of the FIFA Dispute Resolution Chamber (the “DRC”) or the arbitrators of the Court of Arbitration for Sport (the “CAS”), when calculating the relevant amounts. Unfortunately, this rather unsatisfactory process continues to apply today with respect to breaches of contract effected by players.

This article will consider the differing approaches taken by the DRC (at first instance) and the CAS (on appeal) to this issue, highlighting the uncertainty they create for players and clubs, and the financial implications thereof.

2. CALCULATING COMPENSATION – DRC VS CAS

The main purpose of the RSTP is to ensure contractual stability. As the CAS panel in CAS 2008/A/1519 & 1520 Matuzalem & Real Zaragoza v. FC Shakhtar Donetsk & FIFA (“Matuzalem”) held, “any party should be well advised to respect an existing contract as the financial consequences of a breach or termination without just cause would be, in their size and amount, rather unpredictable”.

The CAS has therefore analysed the issue of compensation through the prism of “positive interest”, i.e. that compensation “shall basically put the injured party in the position that the same party would have had if the contract was performed properly, without such contractual violation to occur”.

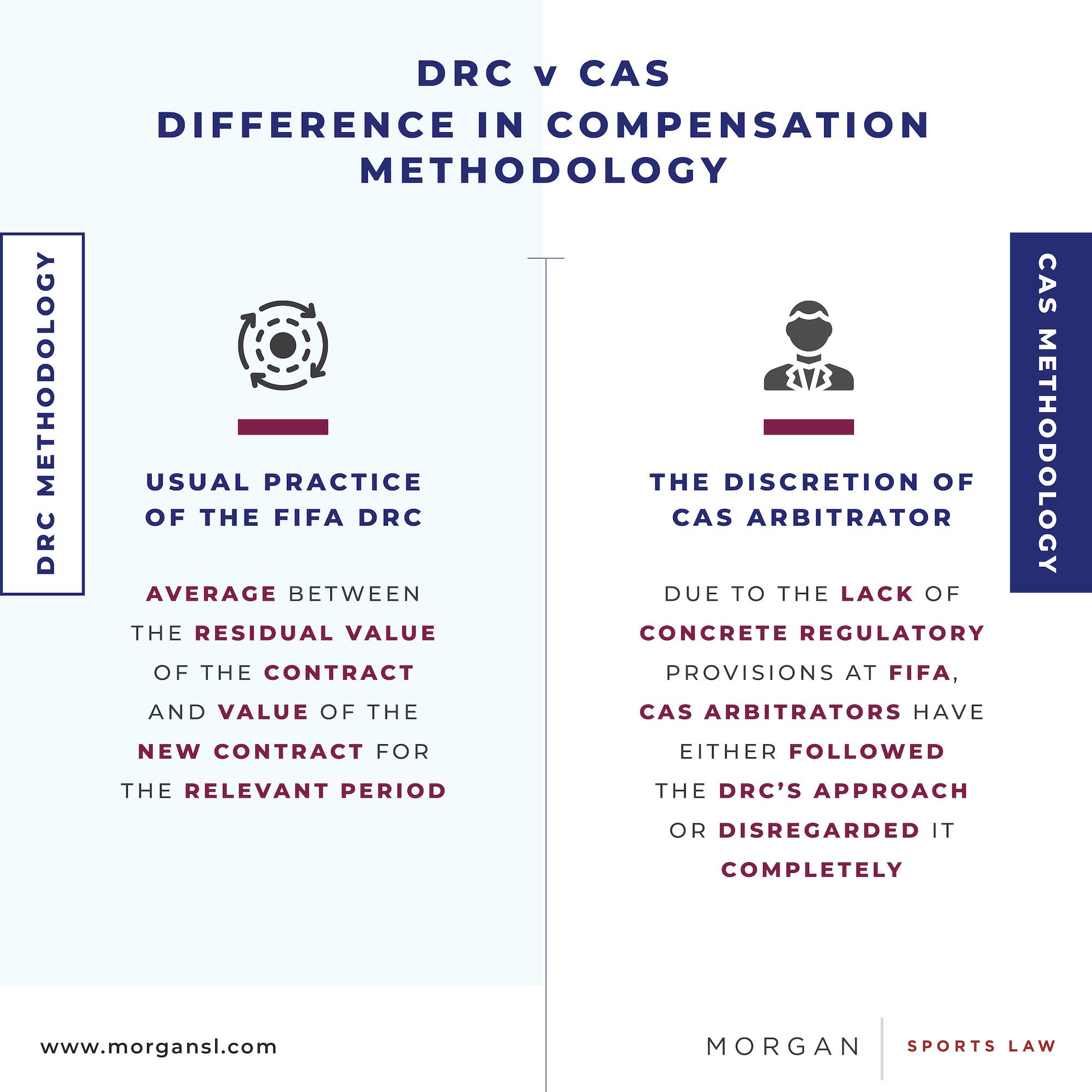

By contrast, the DRC judges will generally calculate compensation owed by players by taking the residual value of the breached contract and the value of of the new contract (for the period during which the prematurely terminated contract would have been valid) and calculating the average between those two figures. This approach is fairly well-established and provides players with some semblance of predictability.

However, while compensation payable by a club to a player for breach of contract is always limited to the residual value of the contract, no such rule exists for players. In any event, as will be seen below, the DRC can depart from its general practice.

Moreover, at CAS level, the calculation of compensation is generally performed by reference to the Matuzalem approach, which lacks certainty. Given the lack of a clear calculation methodology in the RSTP, the discretion of CAS arbitrators remains significant when compensation is owed to a club by a player for a breach of contract.

3. RECENT EXAMPLES OF THE DIFFERENT APPROACHES AT CAS AND THE DRC

Several recent cases highlight the uncertainty propagated by the current approaches to the calculation of compensation owed to clubs by players. Each will now be considered in turn.

a) The Matías Ezequiel Suárez case (CAS 2018/A/5607)

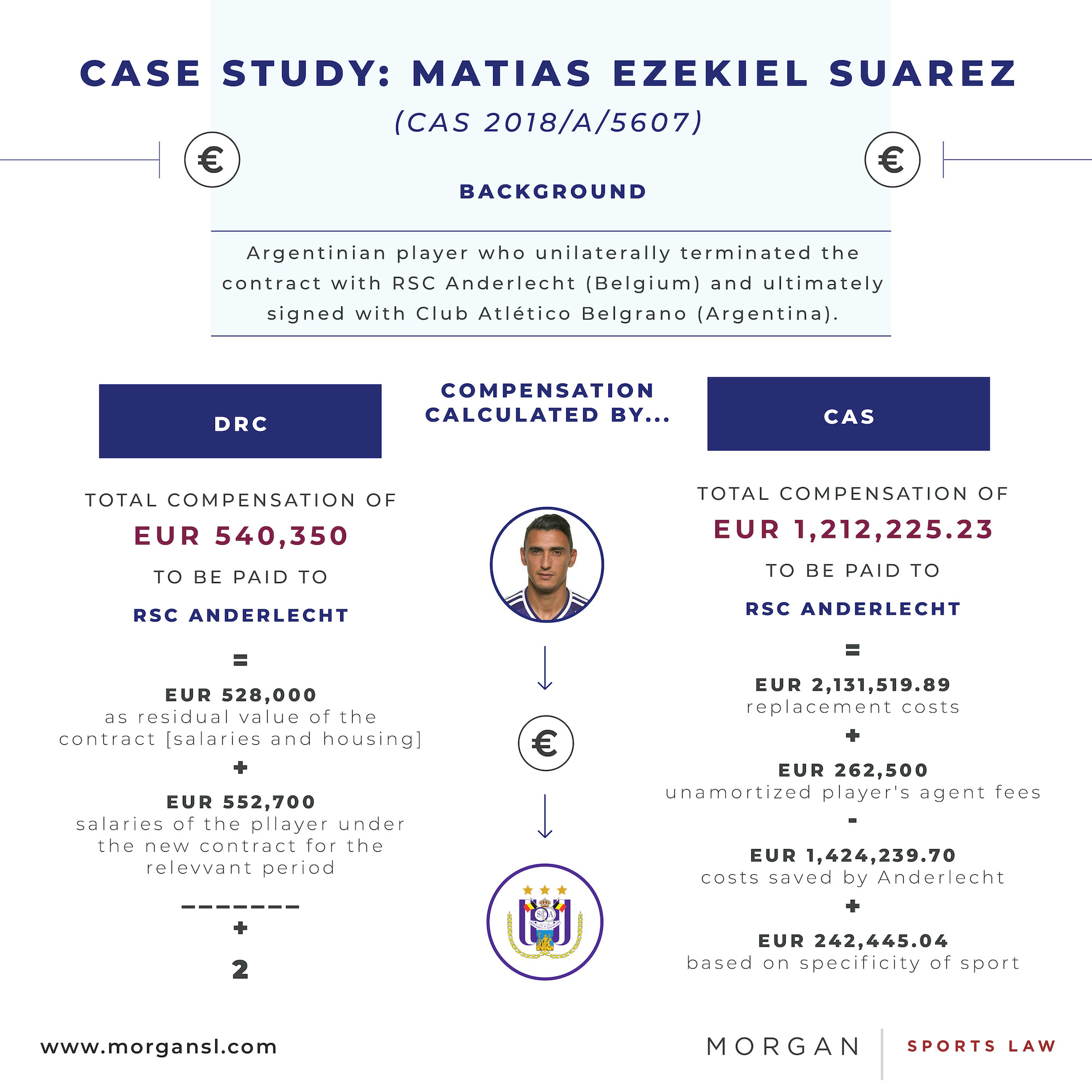

In this case, the DRC at first instance calculated the amount of compensation owed to Mr Suárez’s former club (following his termination without just cause) by reference to the average between the remaining value of the breached contract and his salary under the new contract for the overlapping period, in accordance with its general approach. The total compensation due was thus calculated as being EUR 540,350.

However, on appeal, the CAS (partially) upheld the old club’s appeal and awarded it compensation of EUR 1,212,225.23, disregarding the DRC’s calculation and performing its own calculation, as follows:

- Replacement costs (i.e. the club’s costs in replacing Mr Suárez);

- Plus unamortized agent’s fees (which had been paid by the old club to the player’s agent);

- Minus costs saved by the old club by virtue of Mr Suárez’s departure;

- Plus an amount of EUR 242,445.04 on the basis of the specificity of sport (in view of the specific timing and circumstances of the termination).

Aside from the obvious difference in approach to that of the DRC, the CAS panel’s use of replacement costs here was surprising. The general understanding for use of such costs in the compensation calculation is that the club must prove that the new player was hired specifically to replace the player who left which, as the CAS held in Matuzalem:

requires not only that the players are playing in more or less the same position on the pitch (e.g. it is hard to prove that a forward would substitute a goalkeeper or a defender), but also that the club decided to hire the new player because of the termination by the other player.

In Mr Suárez’s case, several players left the club at the same time as him, making it difficult to establish that the new player would have been specifically acquired to replace Mr Suárez, as opposed to another player, particularly given that players can play in several positions (while, for example, a goalkeeper cannot).

a) The Samman Ghoddos case (06191776-E & CAS 2019/A/6463 & 6464)

This second case concerned a claim filed by Spanish club, Huesca SD, against Mr Ghoddos, after he initially signed an employment contract with them, to transfer from the Swedish club, Ostersunds FC. After Ostersunds FC received a more generous transfer offer from French club, Amiens SC, Mr Ghoddos terminated his contract with Huesca SD.

The DRC found that the player had terminated without just cause and was therefore liable for compensation to Huesca SD. However, departing from its more usual practice, in view of the specific circumstances of the case, the DRC used the player’s market value at the time of the breach as an objective criterion to determine the amount of compensation. The DRC therefore calculated the compensation as being the transfer fee paid by Amiens to Ostersunds, i.e. EUR 4,000,000.

However, on appeal before CAS, the panel held that Huesca SD had failed to demonstrate that it had suffered any damage and therefore awarded no compensation. While Article 17 of the RSTP does not seem to take account of “damage suffered” for the purpose of calculating compensation, this is not the first time the CAS has deemed that proving loss is necessary.

b) CAS 2020/A/7029 (unpublished)

In CAS 2020/A/7029, the CAS panel went even further in its reading of Article 17 of the RSTP. It deemed that the average of the residual value of the breached contract and the value of the new contract for the overlapping period was too low. As such, notwithstanding the fact that Article 17 of the RSTP explicitly excludes training compensation from the calculation of compensation for breach of contract, the CAS panel added the amount of training compensation that the club should have received from the new club, had a transfer taken place.

As a result, the player ended up having to pay his former club an amount of compensation four times higher than that which he would have paid in accordance with the DRC’s general practice.

4. CONCLUSION

As can be seen from the examples discussed above, the compensation to be paid by players to clubs in the event of the termination of their contracts without just cause remains largely unpredictable. Further, given the sums involved, the differences between the various approaches to the calculation of such compensation can be hugely significant for players.

Though one can appreciate that the primary objective of Article 17 of the RSTP is to protect contractual stability, it is difficult to understand why players are subject to such uncertainty against clubs when it comes to foreseeability of the financial consequences of their breach of contract.

It can only be hoped that FIFA will rectify this disparity in treatment as soon as possible: preferably by ensuring that players are given a clear and predictable framework with which to understand the financial consequences of any breach of contract on their part.

Footnote

1. Article 17 RSTP applies in international disputes in the absence of contractually agreed terms in a contract dealing with termination.

2. Mitigation will be considered if player finds a new contract for the overlapping period of the two contracts (taking into account the initial term of the breached contract). Additional compensation may also be awarded in the event of overdue payables, but this will still be limited to the residual value of the contract.

3. Prior to June 2018, Article 17(1) of the RSTP provided that (emphasis added): […] compensation for the breach shall be calculated with due consideration for the law of the country concerned, the specificity of sport, and any other objective criteria. These criteria shall include, in particular, the remuneration and other benefits due to the player under the existing contract and/or the new contract, the time remaining on the existing contract up to a maximum of five years, the fees and expenses paid or incurred by the former club (amortised over the term of the contract) and whether the contractual breach falls within a protected period.Such compensation due to a player would then be limited to the residual value of the contract that was prematurely terminated as a maximum amount.

4. See Matuzalem at ¶ 43

5. The term “compensation” here means compensation generally in breach of contract claims, whether such breach was committed by players or by clubs.

6. See Matuzalem at ¶ 40. Matuzalem constituted an evolution of the jurisprudence from the CAS in Webster (CAS 2007/A/1298, 1299 & 1300), where the CAS panel attempted to specify how compensation had to be calculated in the case of a breach of contract, by reference to the sole residual value of said contract.

7. To this average, the DRC can will also add any unamortised amounts paid to acquire the services of the player (i.e. any unamortised transfer fee and unamortised agent fees).The DRC might also recognise replacement costs, but only where there was proof that the replacement player was acquired specifically to replace the departing one. The CAS has applied such an approach in CAS 2010/A/2145, 2146 & 2147.

8. See Matuzalem at ¶ 90.

9. See CAS 2004/A/662 and CAS 2015/A/4352 & 4353 (both unpublished); and CAS 2012/A/2818.