The new FIFA rules concerning the loan of players – contractual consequences for players

- INTRODUCTION

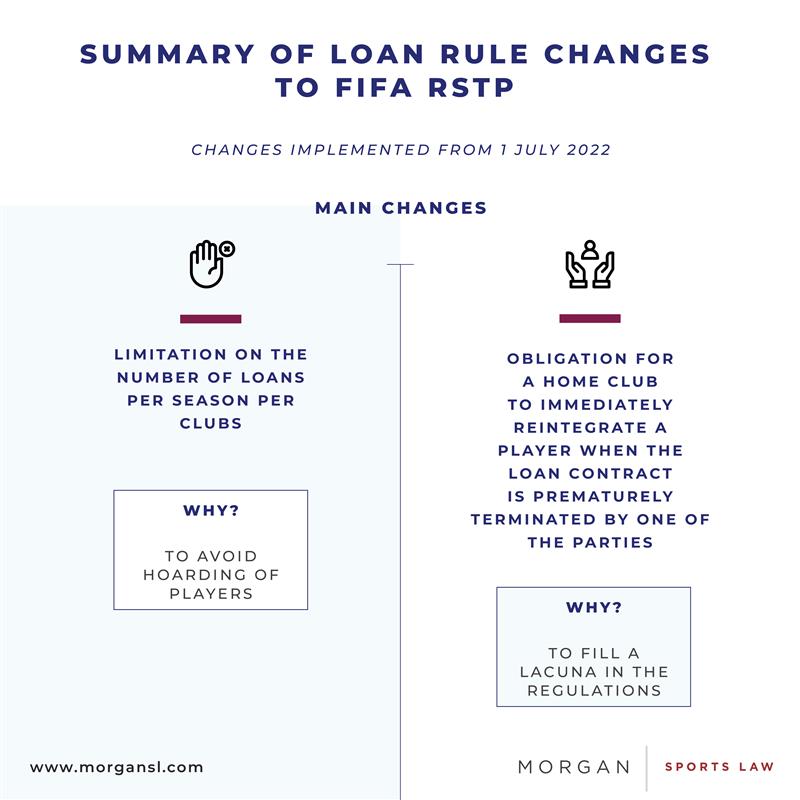

At FIFA level, loans are regulated by the Regulations on the Status and Transfer of Players (the “RSTP”) – particularly Article 10. In the July 2022 version of the RSTP (the “New RSTP”) Article 10 has been significantly modified in order to create a “clear and stable structure” so as to ensure the development of young players whilst “promoting competitive balance and preventing the hording of players”.

Although, the new loan regulations will technically only govern international loans, national member associations (such as The FA) will need to ensure that their national rules (including their national rules as to loans) comply with the New RSTP by 1 July 2025.

The best known change brought in by the New RSTP is the introduction of a limit on the number of loans which can be concluded by a club each season. However, the New RSTP makes further changes to the loan system, some of which may have significant contractual consequences for players.

2. FURTHER NOTABLE CHANGES

It is still not a requirement for players to be parties to loan agreements. However, the New RSTP, in recognition of what was previously standard practice, require a player and the club they join on loan (the “Loanee Club”) to enter into a written contract covering the duration of the loan.

In terms of duration, whilst previous editions of the RSTP only provided for a minimum loan duration, the New RSTP also provide that a loan’s maximum duration is one year. This is intended to limit certain clubs’ practice of keeping a player under contract whilst sending them to play for several seasons at a Loanee Club. It is however still possible for a player to stay on loan for longer than a year, as a loan contract renewal (of a maximum duration of one year) is permitted with the written agreement of the player.

The New RSTP also provide that during the loan “the contractual obligations between the professional and the former club shall be suspended unless otherwise agreed in writing”. This means that the player should only owe contractual obligations towards their Loanee Club during the loan. However, the New RSTP still permit the player’s club of origin (the “Home Club”) to pay part of the player’s remuneration during the loan, as is common practice.

3. CONSEQUENCES UNDER THE NEW RSTP WHERE THE LOAN CONTRACT HAS BEEN TERMINATED

- a) The Home Club’s obligation to take back a player

The most significant clarification made by the New RSTP relates to the contractual consequences of a premature termination of the employment contract signed between the player and the Loanee Club. In such circumstances, the Home Club will be obliged to take the player back immediately upon the request of the player. From that moment on, the original employment contract that had been suspended for the duration of the loan will be in force, such that the Home Club must pay the player’s wages.

Although it is not spelled out within the rules as to loans, it is the author’s view that, if in such circumstances the Home Club refuses to immediately reintegrate the player, a tribunal would likely deem the original contract to have been unilaterally terminated by the Home Club, such that the consequences under Article 17 of the RSTP (for termination without just cause) will apply.

- b) Financial consequences following the premature return of a player to his Home Club

The New RSTP are unclear as to the financial and/or sporting consequences which will result when there has been a unilateral termination of the employment contract between the player and the Loanee Club.

This may give rise to some issues. For example, where a player has terminated their contract with the Loanee Club without just cause such that their Home Club has been “forced” to reintegrate them, what would be the position of the Home Club? In accordance with Article 17 paragraph 2 of the RSTP “if a professional is required to pay compensation, the professional and his new club shall be jointly and severally liable for its payment”. “New club” is defined in the RSTP as “the club that the player is joining”, and the FIFA Dispute Resolution Chamber (“DRC”) has consistently held that the new club is the first club with which the player was registered following the breach of contract. Therefore, in the contemplated scenario, the Home Club could be jointly liable to pay any compensation that the player might have to pay to the Loanee Club, notwithstanding that it had no choice but to reintegrate the player. Perhaps surprisingly, such an approach has been taken in the past by the Court of Arbitration for Sport (the “CAS”).

It thus seems that a player’s unjustified termination of the loan contract could put their Home Club in an impossible situation. Either it takes the player back immediately (as required by the New RSTP) and risks being liable to the Loanee Club for the player’s breach, or it refuses to do so, which could amount to a breach of its contract with the player. It will therefore be interesting to see how the DRC decides any such cases.

- c) The new concept of compensation introduced by Article 10 paragraph 5 c)

At Article 10 paragraph 5 c), the New RSTP permit the Home Club to “seek compensation resulting from its obligation to reintegrate the professional”.

The New RSTP do not specify from whom the Home Club may seek this compensation. However, we assume that compensation would be sought from the player or the Loanee Club, depending on which party breached the employment contract such as to cause the early return of the player.

Article 10 paragraph 5 c) further provides that the minimum compensation payable shall be the amount the Home Club must pay the player between the date of reintegration and the original completion date of the loan.

Accordingly, in a case where the player breached the loan contract, will it be the case that the Home Club, now jointly and severally liable to pay the compensation owed by the player to the Loanee Club, could take account of that liability when calculating the compensation to be sought from the player? In fact, the Home Club could end up having to pay a player’s salary (following the player’s unjustified termination of a loan contract) whilst pursuing the same player for compensation in relation to those payments (which would not have been required had the player not terminated the loan contract).

- d) Jurisdiction

Finally, another issue which may arise under the New RSTP is where the Home Club and the player have the same nationality and the player has been loaned to a club in another country.

In such circumstances, any claim of the Loanee Club against the player for breach of the contract would fall within the competence of FIFA, as such a claim would have an international dimension.

However, any claim of the Home Club against the player for compensation in application of Article 10 paragraph 5 c) would not have an international dimension, such that, despite being based on FIFA regulations, such a claim would seemingly not fall within the competence of FIFA.

4. CONCLUSION

The changes to the loan rules represent a long overdue attempt to impose a clear and stable structure in order to avoid excessive and abusive practices, but, unfortunately, some of the changes raise more questions than answers.

Accordingly, that lack of clarity, and given some of the consequences that could arise from an early termination of the loan contract (as summarised above), clubs might be less eager to loan young players abroad.

Thus, the New RSTP may prove to stifle the movement of young players. However, and on the other hand, New RSTP ought to strengthen the principle of contractual stability.

Footnote

1. See FIFA Circular 1796

2. In accordance with Article 1 paragraph 3 b) of the New RSTP

3. See Article 1 para. 3 b) of the New RSTP

4. This limitation will be applied gradually, so that in season 2022/2023 a maximum of eight professional players may be loaned out by a club (with the same restriction applying as regards the loaning in of players), in season 2023/2024 the limit will be seven players, and finally in season 2024/2025 the limit will be six players. At domestic level Members Associations can set the limit at a different level (e.g. nine players), but FIFA has stated that any alternative limit must be consistent with the main purpose of the limitation.

5. In accordance with Article 10 para. 1 d) “Subject to article 5 paragraph 4, a loan agreement may be concluded for a minimum duration of the time between two registration periods and a maximum duration of one year. The end date shall fall within one of the registration periods of the association of the former club. Any clause referring to a longer duration of the loan shall not be recognised”.

6. See Article 10 para. 1 e) " A loan agreement may be extended, subject to the above minimum and maximum durations, with written consent of the professional”.

7. See Article 10 para. 1 c)

8. Article 10 para. 4 “Where the contract between a professional and the new club has been unilaterally terminated prior to the completion of the duration agreed in the loan agreement: a) The professional has the right to return to the former club; b) The professional must immediately inform the former club of the premature termination and whether they intend to return to the former club; c) If the professional decides to return to the former club, the former club must reintegrate the professional immediately. The contract which was suspended during the loan shall be reinstated from the date of reintegration, and in particular, the former club must remunerate the professional; d) Rules governing at national level must be determined by the association in agreement with domestic football stakeholders.”

9. Whist the player has to be reintegrated immediately, his registration with the Home Club would in theory only be possible if the registration window of the Home Club is open. If the registration window is closed, the player would need to demonstrate prima facie that he had just cause or that the Loanee Club had no just cause to terminate the contract (see the Explanatory Notes on the New Loan Provisions in the Regulations on the Status and Transfer of Players. In that case, the Home Club would be forced to pay a player who cannot render any services since he would not be registered.

10. See FIFA’s Commentary on the FIFA Regulations on the Status and Transfer of Players Edition 2021 at p. 172

11. See CAS 2016/A/4408 Raja Club v. Baniyas FC & Benlamalen. However, in a more recent case, the DRC held that due to the “truly exceptional circumstances”, the Home Club should not be jointly and severally liable (see DRC decision 04190658 of 11 April 2019 as the player had only been reintegrated at the end of the original loan spell by his Home Club [i.e. not immediately following the player’s early termination of the loan], and the DRC considered that the Home Club had no choice but to re-register the player at that time).

12. In accordance with Article 22 paragraph 1a) of the New RSTP since there would be neither a dispute “in relation to the maintenance of contractual stability (articles 13-18) where there has been an ITC request” nor “a claim from an interested party in relation to said ITC request”. However, given that the ITC will have returned to the Home Club, the DRC might consider that enough for it to have jurisdiction.