Reconsidering Rule 50

Rule 50 of the Olympic Charter prohibits any “kind of demonstration or political, religious or racial propaganda…in any Olympic sites, venues or other areas”. Guidance issued by the IOC’s Athlete Commission in January 2020, ahead of the planned summer Olympic Games in Tokyo, clarified that the prohibition extends to the act of kneeling; the now ubiquitous gesture for acknowledging the existence of racial inequality. In light of recent events, and in particular the stance adopted by other prominent sports governing bodies, is the IOC’s position tenable?

It is an irony not lost on the black and minority ethnic community. That it was amidst the seemingly all-encompassing turmoil caused by the Covid-19 pandemic, that their complaints of historic injustices and current racial inequality reached a frequency that could no longer be ignored. Those complaints, of course, most recently arising out of the senseless killings of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor and George Floyd earlier this year.

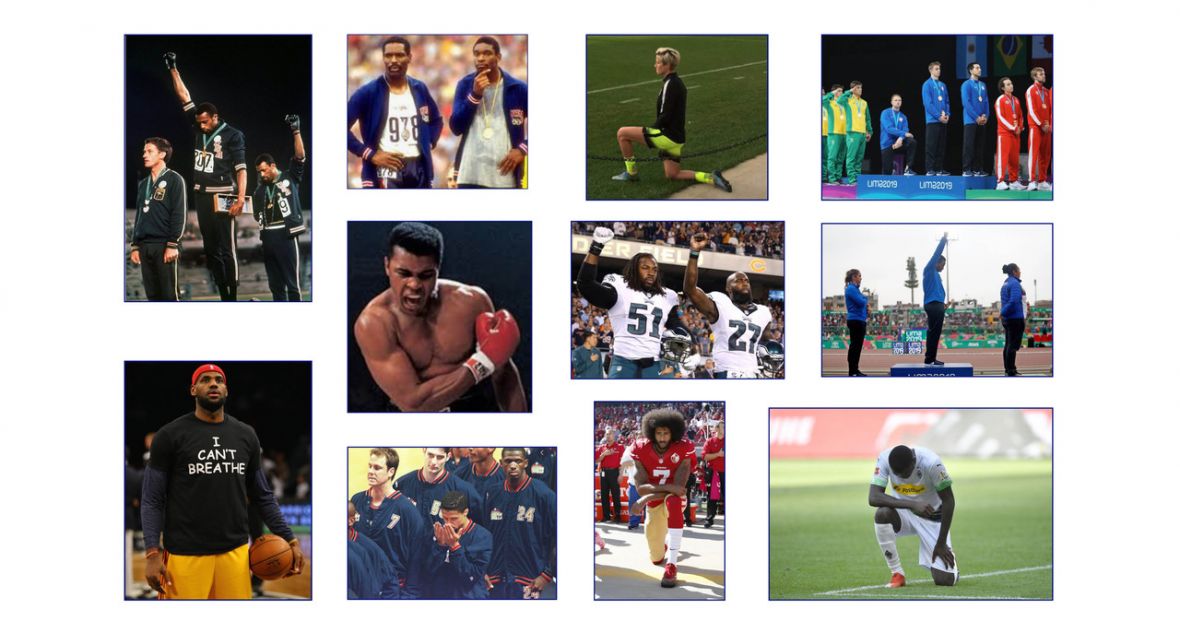

The wider issues that have arisen from George Floyd’s death have plainly resonated with professional athletes – a group often (unfairly) maligned as being so insulated by the rewards of their profession that they are detached from real world issues. There is no mistaking, however, that on this issue, athletes are making themselves heard like never before. Some sports leagues, associations and governing bodies will undoubtedly be hoping that the uproar will have largely dissipated by the time competition restarts in their respective arenas. After all, and rather absurdly, athlete protests seeking racial equality have long been treated as a thorny issue. One need only consider that the simple – and now ubiquitous – act of kneeling, first performed by former NFL quarterback Colin Kaepernick fewer than 4 years ago, cost Kaepernick his career, caused a political storm, created public division and pitted players against the league.

In May 2018, NFL team owners unanimously voted to prohibit the act of kneeling during the playing of the U.S. national anthem. On 6 June 2020, after pressure from players, the Commissioner of the NFL accepted that it had been wrong of the league to seek to subvert player protests; adding that the league now supports peaceful protest. The significance of the reversal is difficult to overstate although what it means in practice will not be known until the NFL season begins in the autumn.

Given the events of the past few weeks, it is difficult to understand why the International Olympic Committee (“IOC”) has allowed itself to lag behind the rest of the sporting world. On 1 January 2020, its President, Thomas Bach, used his New Year’s Address to the ‘Olympic family’ to decry the growing politicisation of sport, declaring that “the Olympic games must never be, a platform to advance political or any other potentially divisive ends” (emphasis added). On 9 January 2020, the IOC’s Athlete Commission, published guidance on Rule 50 of the Olympic Charter which has long prohibited any, “…kind of demonstration or political, religious or racial propaganda… in any Olympic sites, venues or other areas” (the “Guidance”). The Guidance provides that the aims of the Rule are, inter alia, to:

- Ensure observance of the fundamental principle that sport is neutral and must be separate from political, religious or any other type of interference.

- Ensure that the focus for the field of play and related ceremonies is on celebrating athletes’ performance, and showcasing sport and its values.

- Preserve the dignity of the competition or the ceremony in question from destruction.

The Guidance goes on to state that:

When an individual makes their grievances, however legitimate, more important than the feelings of their competitors and the competition itself, the unity and harmony as well as the celebration of sport and human accomplishment are diminished.

Whilst the Guidance explains that athletes will be able to express their views during press conferences and via traditional and social media, it also expressly states that “displaying any political messaging, including signs or armbands or making gestures of a political nature, like a hand gesture or kneeling” are each forms of demonstration that will attract censure.

Past instances in which athletes and even host nations have used the Olympic Games to further political views are too plentiful to discuss meaningfully in this article. Arguably the most famous demonstration, and certainly the most relevant in the current context, was by U.S. athletes Tommie Smith and John Carlos at the 1968 Olympic Games. As is well known, both men were expelled from the 1968 Games after each held aloft a black leather glove-clad fist on a podium during a medal ceremony. The IOC’s view at the time was that the men had committed, “a deliberate and violent breach of the fundamental principles of the Olympic spirit”. The then IOC president, Avery Brundage, criticised Smith and Carlos for politicising the Olympic Games (notwithstanding that German athletes performed the Nazi salute on the podium at the 1936 Olympic Games, during Brundage’s tenure, without censure).

Where the IOC erred in 1968, as it does now, is to characterise the issue of racial inequality as political and, worse still, to equate demonstrations for racial equality to “propaganda”.

It is possible to read Rule 50, and its predecessors, in charitable and cynical lights alike. Read in the former light, it is a laudable attempt to ensure that, in a world of complex conflicts and increasingly polarised political views, athletes can exist in a meritocratic vacuum, free from the (often cruel) realities of the world. It also seeks to ensure that the platform of the Olympic Games is not (further) abused for dubious political aims.

However, what the IOC must come to recognise, as other sports bodies have, is that, as Smith and Carlos did with their gesture, those athletes who would propose to kneel would be doing so to draw attention to a mere fact, not a political view. That fact being that, by reason only of the complexion of their skin, the lives of a group of people have historically been treated as being less valuable than their counterparts of other complexions and, over time, that has led to inequality. The open acknowledgment of this fact ought not be controversial or thought capable of destroying the “dignity” of the Olympic Games. Should the IOC’s position remain as set out in the Guidance, the clear implication will be that the right of athletes to peacefully express grievances against racial inequality are of lesser import than the feelings of “competitors and the competition itself” and “the celebration of sport and human accomplishment”.

Although the Guidance had already drawn criticism when first published, it has come under renewed fire in the wake of Mr Floyd’s death. The IOC’s initial reaction to the protests around the world was to confirm, on 9 June 2020, that the Guidance would remain in place for the postponed Olympic Games. The next day, following a backlash, the IOC released a statement which made no mention of Mr Floyd or the protests, and instead appeared designed to sell the virtues of the Olympic Games as “a very powerful global demonstration against racism and for inclusivity” and “a celebration of the unity of humankind in all our diversity”. The statement did not indicate any change in position and, instead, noted that “[t]he IOC Executive Board supports the initiative of the IOC Athletes’ Commission to explore different ways of how Olympic athletes can express their support for the principles enshrined in the Olympic Charter, including at the time of the Olympic Games, and respecting the Olympic spirit”. Thus, the issue is now apparently in the hands of the IOC Athlete Commission, with Mr Bach claiming that “they are giving directions or instructions in this respect”.

The IOC’s foot-dragging appears even less enlightened when compared to the approach adopted by professional football’s governing bodies. Notwithstanding that the International Football Association Board’s Laws of the Game prohibit players from revealing “undergarments that show political, religious, personal slogans, statements or images” (Law 4.5), FIFA’s president implored national associations not to sanction players who have displayed messages of sympathy for George Floyd or made gestures acknowledging the issue of racial injustice during matches. Accordingly, the German FA announced that it would not sanction players who had displayed such messages or made such gestures during Bundesliga matches. The English Premier League has gone a step further, collaborating with players on an initiative to wear the phrase ‘Black Lives Matter’ on their jerseys in place of their names and on a patch on their jerseys thereafter.

With the postponement of the Olympic Games originally scheduled for this year, the IOC has been afforded an opportunity to reconsider Rule 50 of its Charter and the accompanying Guidance. Given recent events, it is difficult to imagine that the IOC – already facing claims that it is out of touch – will not make an exception for peaceful demonstrations against racial inequality. In doing so, it would be implicitly recognising what should already be obvious; objecting to racial inequality is not “propaganda”.

Authored by

Nii Anteson

Associate

With editorial input from Mike Morgan.