RFC Seraing v. FIFA: A Game-Changer for Sports Disputes?

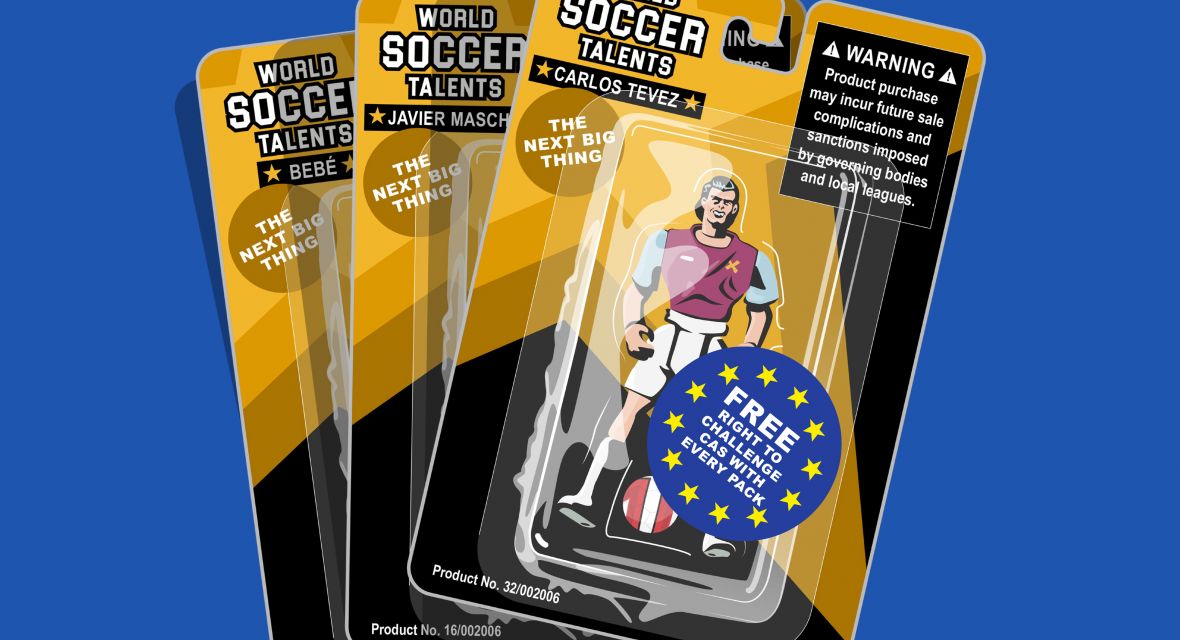

Third Party Ownership of players’ economic rights (“TPO”) has long been a controversial issue in football and has been prohibited by FIFA since 2015. Ten years on, the legal challenge to FIFA’s TPO rules has finally reached the Court of Justice of the European Union (“CJEU”) and, following the Advocate General’s opinion of 16 January 2025 (available here), the case looks set to transform the system of international sports arbitration as we know it.

Background

By way of overview, in 2015, Belgian second division club RFC Seraing was found to have violated FIFA’s prohibition of TPO, owing to agreements it had entered into with the Maltese investment company, Doyen Sports. FIFA sanctioned RFC Seraing with a two-year player registration ban and a CHF 150,000 fine.

The club appealed to the Court of Arbitration for Sport (“CAS”) and argued that FIFA’s TPO rules were unlawful, inter alia, on the basis they were non-compliant with EU free movement and competition law. However, in March 2017, CAS dismissed the appeal and upheld the legality of FIFA’s TPO rules.

Under the FIFA Statutes and Article R59 of the CAS Code, CAS awards are final and binding, with the exception of an appeal to the Swiss Federal Tribunal, which can only be made on very limited grounds, concerning formal aspects rather than allowing a revision of the award as to its merits (i.e., no full review). RFC Seraing duly appealed to the Swiss Federal Tribunal but, in February 2018, this was rejected.

However, in 2015, the club had also brought concurrent proceedings in the Belgian courts, alongside Doyen Sports, against FIFA, UEFA and the Belgian FA, seeking a ruling that FIFA’s TPO rules violate EU law, and claiming damages.

The initial claim before the Brussels Commercial Court failed, so the club then appealed to the Brussels Court of Appeal. However, by the time the appeal was heard, the CAS proceedings had concluded, and the Court of Appeal held that the matter was therefore res judicata, such that it could not be re-litigated before the national courts.

Nevertheless, RFC Seraing and Doyen Sports appealed again, this time to the Belgian supreme court (the Court of Cassation), arguing, inter alia, that the CAS award could not have res judicata effect because the CAS does not provide effective judicial protection of rights under EU law.

The Court of Cassation referred this question – whether CAS awards have res judicata effect on matters of EU law – to the CJEU for a preliminary ruling.

Opinion of Advocate-General Ćapeta

On 16 January 2025, Advocate-General Ćapeta issued her opinion on the matter, concluding that CAS awards issued pursuant to FIFA’s rules cannot have res judicata effect on matters of EU law.

On the contrary, the Advocate-General held that CAS awards must be subject to full review by national courts in Member States on questions of EU law. This is because such courts are able to refer these questions to the CJEU in order to guarantee the effective judicial protection of EU law rights, as required by Article 267 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the EU.

The CAS is subject only to the jurisdiction of the Swiss Federal Tribunal, which is not bound by EU law, as Switzerland is not an EU Member State. Therefore, prima facie, effective judicial protection of EU law rights cannot be guaranteed.

However, as the Advocate-General recognised, it has been accepted in the context of commercial arbitration that parties are free to agree to exclude the jurisdiction of national courts, save to the extent that to do so would violate EU public policy, and that in these circumstances arbitral awards will ordinarily have res judicata effect.

Yet, building on the recent decision of the CJEU in Case C‑124/21 P International Skating Union, Advocate-General Ćapeta distinguished CAS arbitration under FIFA’s rules on the following two grounds.

First, the FIFA Statutes provide that the CAS shall have exclusive jurisdiction over disputes under FIFA’s rules and regulations and expressly prohibit any “recourse to ordinary courts of law”. Accordingly, the Advocate-General held that the parties “do not freely choose to exclude the application of some EU rules” and, as such, “mandatory sports arbitration requires rules offering more generous access to justice and a broader scope of review”.

Second, CAS awards rendered pursuant to the FIFA Statutes can be enforced by FIFA without recourse to any national court, owing to the enforcement mechanism of sporting sanctions provided for in FIFA’s rules and regulations. This is significant because it further excludes the possibility of review before national courts, at the enforcement stage.

FIFA’s self-enforcing regulations are markedly different from ordinary commercial arbitration, in which arbitral awards must be enforced through national courts, and a party wishing to resist enforcement on the basis of non-compliance with EU law can raise these arguments before the enforcing national court, which may then refer questions of EU law to the CJEU. Thus, in the absence of such safeguards, FIFA’s enforcement rules further deprive participants of the right to effective judicial protection under EU law.

As such, the Advocate-General concluded, at para. 105, that:

The principle of effective judicial protection therefore requires a direct judicial path to assess and, if necessary, to prevent the application of FIFA’s rules that are contrary to EU law. An arbitral award proclaiming the conformity of FIFA’s rules with EU law cannot stand in the way of a national court’s power to review such conformity on its own, referring the question of interpretation of EU law to the Court if necessary.

What does this mean for international sports arbitration?

The Advocate-General's opinion, although non-binding, could lead to a dramatic shift in sports arbitration. If the CJEU follows the opinion (as it does in 90% of cases), the decision will be seen as a further victory for athletes, clubs, and other sports participants – following a series of recent decisions challenging the dominance of sports governing bodies like FIFA. Indeed, the case could redefine how disputes between the regulators and the regulated in football and other sports are resolved.

In particular, it raises serious questions about the role of the CAS as the go-to forum for international sports disputes (in particular, vertical disputes, where the governing body is defending its own interests and rules) and may prompt more sports-related legal challenges to be litigated in national courts within the EU.

One potential solution could be for the CAS to revise its rules, allowing parties to choose an EU Member State as the seat of arbitration, with the option for national courts in that Member State to review awards on EU law grounds.

UEFA has already taken steps toward this direction – following the International Skating Union case – providing an option for disputes to be heard by CAS in Dublin and providing that awards could then be challenged on EU public policy grounds. However, it is not clear that such an arrangement is compatible with the CAS Code, nor that the scope of review will be sufficient in light of the Advocate-General’s recent opinion.

European and international sports federations will now likely have to rethink their approach to dispute resolution, to ensure compatibility with EU law and ensure adequate access to justice for all parties, while athletes and other participants seeking to challenge such federations may now seek to place a renewed emphasis on EU law arguments.

However, this may cut both ways, as federations, too, may be able to re-open cases which otherwise would have concluded. The time and cost implications of protracted litigation before national courts must also not be underestimated.

Indeed, despite the criticisms occasionally directed at the CAS, there is no doubt that a single, centralised forum for international sports dispute resolution is a good thing for all parties and that, without it, there would be a real risk of developing inconsistent jurisprudence.

Therefore, if the CJEU follows the opinion of Advocate-General Ćapeta in RFC Seraing, international sports arbitration will be set for a significant transformation, but care will need to be taken to ensure that it does not become unduly fragmented.

Authored by

Omar Ongaro

Special Counsel

Ben Cisneros

Associate

Jonathon Huggett

Paralegal

Footnote

1. Case C-600/23 RFC Seraing v. FIFA et al., para. 112

2. Case C-600/23 RFC Seraing v. FIFA et al., para. 98

3. Case C-600/23 RFC Seraing v. FIFA et al., para. 105

4. Case C-600/23 RFC Seraing v. FIFA et al., paras. 100-101

5. See The Elusive Influence of the Advocate General on the Court of Justice: The Case of European Citizenship, Yearbook of European Law, Volume 36, 2017