Under the Microscope: Sport’s Duty of Care in the COVID-19 era

1. INTRODUCTION

Though many in the sports industry are familiar with the term “duty of care”, the way the concept is understood and approached can differ tremendously.

The UK has had its issues in recent years – particularly regarding the treatment of junior athletes on talent pathways – which has raised questions as to whether appropriate welfare structures were/are in place to protect athletes. The COVID-19 pandemic has thrust the concept back into the limelight as decision-makers try to strike a balance between the safe return of sport and avoiding financial ruin.

2. DEFINING DUTY OF CARE

So, what do we actually mean by “duty of care”? Although dictionary definitions generally refer to some type of responsibility or obligation to safeguard others from harm, the concept is best understood (from a legal perspective) in the context of claims in the tort of negligence.

For a negligence claim to succeed, three key limbs must be satisfied. First, the claimant must establish the existence of a duty of care; then prove that the duty was breached; and finally, demonstrate that loss or damage was caused by that breach. So, in what circumstances can a duty exist?

The notion of a duty of care was first articulated in Lord Atkin’s seminal judgment in Donoghue v Stevenson [1932] AC 562 HL, with the formulation of (what was known as) the “neighbour principle”. In effect, the principle provided that any persons making a product, or offering a service, must contemplate the safety of the users of that product or service, regardless of whether a contractual relationship exists.

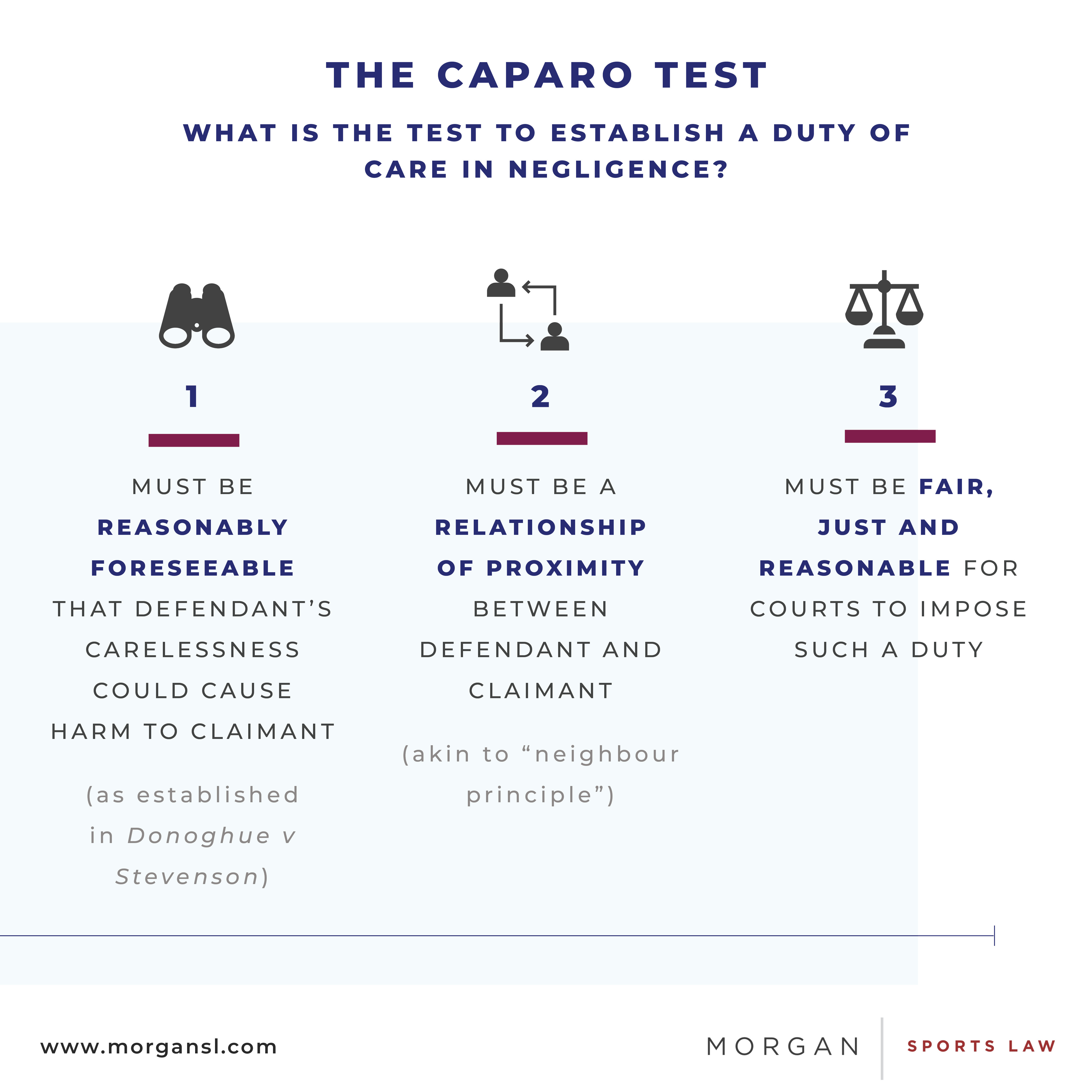

Over time, the principle evolved into the formulation of a three-fold test, derived from the judgement in the House of Lords case of Caparo Industries PLC v Dickman [1990] UKHL 2.

The Caparo test is generally still regarded as good law, albeit two Supreme Court decisions from 2018 (Robinson v Chief Constable of West Yorkshire Police [2018] UKSC 4 and Steel v NRAM Ltd [2018] UKSC 13) have suggested that this three-stage test has its limitations and that an incremental approach based on analogous cases should be preferred.

3. WHO OWES A DUTY OF CARE TO WHOM?

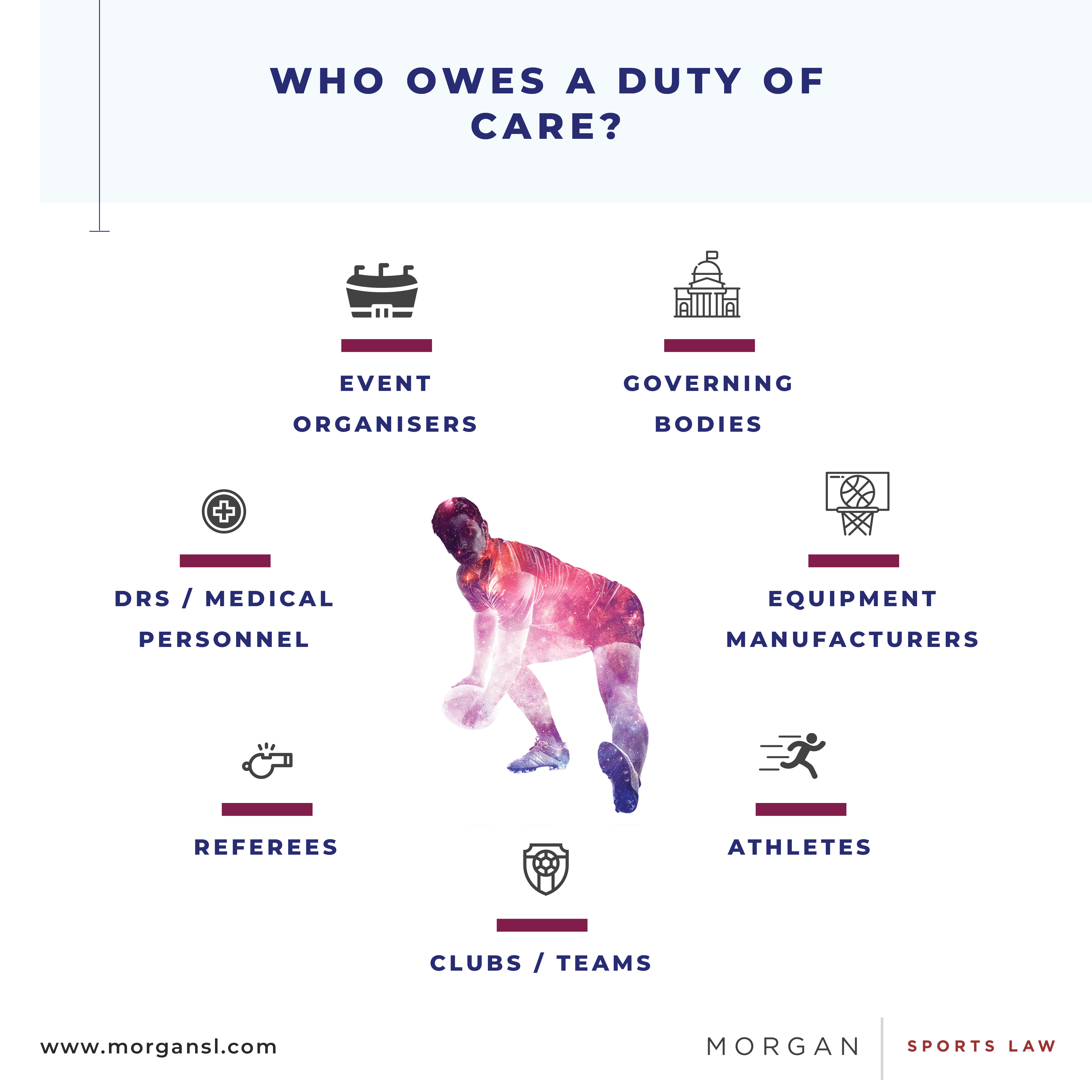

In a sporting context, the English courts have generally been happy to impose a fairly wide scope of duty of care. Briefly, anyone with an official capacity to organise, manage or supervise sport has a duty of care to ensure it is as safe as possible for all participants. As a result, sports governing bodies (“SGBs”), event organisers, equipment manufacturers, clubs, doctors and medical personnel, referees and athletes have all been held to owe a duty of care. This duty is generally owed to athletes, but can also cover officials, spectators and even passers-by (depending on the circumstances).

The duty of care owed by sports event organisers has been the subject of recent judicial examination in England and Wales. The High Court judgment (handed down on 19 May 2020) in Christopher Wells v Full Moon Events Ltd & Another [2020] EWHC 1265 (QB) confirms that event organisers do not have an absolute duty to protect participants against every feasible risk of injury – as that would, amongst other things, negate the social value of the sporting or recreational activity. Instead, the extent of the duty of care owed is based on what steps are reasonable to take in the circumstances, taking into account the specific activities expected to be undertaken, i.e. there is no duty to warn adults against risks that are obvious or inherent in the nature of sport.

The duties owed in certain contexts by one party to another (e.g. employer to employee, landowner or occupier to visitor) also have legislative basis. The Occupiers Liability Act 1957, the Health and Safety at Work Act 1974 and the Corporate Manslaughter and Corporate Homicide Act 2007 each provide potential claimants an alternative route to establishing the existence of duty.

4. COVID-19 PANDEMIC – COULD IT LEAD TO NEGLIGENCE CLAIMS?

In the week preceding the UK Government’s ban on mass gatherings, several high-profile sporting events went ahead in UK. According to Professor Tim Spector, the scientist leading the UK’s largest COVID-19 tracking project, the decision to allow thousands to attend the Cheltenham Horseracing Festival (10-13 March 2020) and Liverpool’s UEFA Champions League tie against Atletico Madrid at Anfield (11 March 2020) “caused increased suffering and death”.

Some of those affected (or the estates of the deceased) may well be considering their options for a claim on the basis that the decision-makers negligently permitted the events to proceed. Satisfying the test for breach of duty – which has both an objective and subjective element to it – will depend, inter alia, on whether relevant SGBs and/or event organisers are deemed to have acted unreasonably in light of matters that were known, or should have been known, to them at the relevant time.

One question that is likely to arise is whether – even in the absence of a government-imposed lockdown – the relevant SGBs and/or event organisers should have taken matters into their own hands by suspending or postponing the competitions/events or, at the very least, taking precautionary measures (e.g. holding the events behind closed doors). Defendants may well take the approach that a breach should not be assessed with the benefit of hindsight but rather whether the approach taken at the time (i.e. when the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases in the UK were a fraction of what they would become, and at a level the UK Government had not deemed to warrant the prohibition of mass gatherings) was reasonable.

Assuming that a claimant was able to prove breach of duty, they would also need to satisfy the two limbs of causation, namely:

- Factual causation – but for the defendant’s breach of duty, on the balance of probabilities, the claimant would not have suffered the relevant damage; and

- Legal causation – the relevant damage suffered was not too remote a consequence of the defendant’s breach of duty.

Thus, a claimant would need to establish first, on the balance of probabilities, that had they not attended the relevant event they would not have otherwise contracted COVID-19. Then, to be entitled to any damages, a claimant would need to establish that the damage they suffered was a reasonably foreseeable consequence of holding the event.

Another pool of potential claimants will be athletes or club staff, whether because they have contracted COVID-19, or because of some damage caused by the return to competition. For instance:

- research conducted by artificial intelligence platform Zone7, has suggested that Premier League players face a 25% increased risk of injury in the remainder of the season due to the revised/truncated fixture list.

- Premiership Rugby has come under recent criticism, from a player welfare perspective, for re-scheduling the remaining seven fixtures of its league season in just a four-week window.

Satisfying causation in such instances would inevitably be a difficult – but not necessarily insurmountable – hurdle to overcome if an injured player were to pursue a negligence claim on such basis. A disproportionate number of injuries might give the Premier League, Premiership Rugby and/or the relevant clubs cause for concern from a liability standpoint.

It is trite law that SGBs, event organisers and/or clubs will not be able limit or exclude liability for any personal injury or death for negligence (under Section 2(1) of the Unfair Contract Terms Act 1977) – for instance, by forcing participants to sign a waiver. However, defendant(s) may nonetheless invoke the principle of volenti non fit injuria (“voluntary assumption of risk”) or a partial defence of contributory negligence. A volenti defence would be predicated on the basis that the claimant(s) were fully aware of the risks of participation (i.e. it was a foreseeable risk in the circumstances).

5. THE IMMEDIATE FUTURE

Over the coming months, every sport will have its own challenges to overcome. A degree of flexibility and innovation will be required, particularly by those entities towards the top of the sporting pyramid, to provide a safe environment for all involved and to thrive in this new world. Several sports have already risen to the challenge, and other will need to follow suit.

Whilst the UK Government’s COVID-19 guidance on the phased return of sport and recreation, which includes guidance for elite sport, may provide some basic signposts for sports to follow, those in charge of sports will do well to bear in mind that what is deemed “reasonable” is a continually evolving metric in this COVID-19 era. That may ultimately mean going further than government recommendations to ensure the safety of all participants.

Authored by

Authored by

Henry Goldschmidt

Associate

Footnote

1. It was no real surprise, therefore, that the UK Government commissioned an independent report into “the duty of care that sport has to its participants” in 2015. The Report, written by Baroness Tanni Grey-Thompson, was published in April 2017.

2. For example: (1) “The legal obligation to safeguard others from harm while they are in your care, using your services, or exposed to your activities.” (Collins Dictionary) (2) “A responsibility to take care over what happens to someone or something.” (Cambridge Dictionary) (3) “A legal or moral responsibility that someone has to make sure other people are safe and well.” (MacMillan Dictionary) (4) “A duty to use care toward others that would be exercised by an ordinarily reasonable and prudent person in order to protect them from unnecessary risk of harm.” (Merriam Webster)

3. English civil law standard of proof (i.e. probability is more than 50%) – a lower standard than the standard of proof under English criminal law (“beyond reasonable doubt”), or applied by the Court of Arbitration for Sport (“comfortable satisfaction”).

4. For instance: (1) Where a case falls within an established category [e.g. actions against public authorities], the existence of the duty should be determined in accordance with principles laid down for that category; (2) Where a case involves a novel situation – where existing principles cannot be readily applied – the law should be developed incrementally by analogy with established categories.

5. In Wells v Full Moon Events & Another [2020] EWHC 1265 (QB), the claimant had alleged that the defendants, the organisers of an off-road motorbike event, were negligent for failing to carry out a proper risk assessment of the course and/or issue the necessary warnings about concealed dangers. The claimant had suffered an accident during the event leaving him with severe spinal injuries. The High Court found the defendants not liable for the accident as the claimant was deemed, by Deputy Judge Michael Bowels QC (at para. 126), to have accepted the risk: “I am satisfied on the basis of claimant’s own evidence, the signing on form and the Indemnity signed by the claimant that he fully accepted there was an inherent risk in motorcycling off-road and that he was aware of those risks.”

6. This hypothesis being based on those locations becoming “hotspots” two weeks after the events given relative spikes in the number of people reporting COVID-19 symptoms and being admitted to hospital trusts in the Cheltenham and Liverpool catchment areas.

7. A breach is when one fails to exercise reasonable care, as judged by the standards of a reasonable person (Hall v Brooklands Auto-Racing Club [1933] 1 KB 205), adjusted to take into account the defendant’s personal situation or characteristics (Dunnage v Randall & Another [2015] EWCA Civ 673).

8. For instance, on 9 March 2020, UEFA announced that the Champions League tie between PSG and Borussia Dortmund would be played without fans – so it was a decision that it was willing to make in the circumstances.

9. It is worth noting that courts have, on occasion, been willing to relax the “but for” test – e.g. in cases where the act in question materially contributed to a claimant’s injury rather than being the sole cause (“material contribution test”). See, for instance, Bailey v Ministry of Defence [2009] EWCA Civ 883, per Waller LJ at para. 46: “If the evidence demonstrates that 'but for' the contribution of the tortious cause the injury would probably not have occurred, the claimant will (obviously) have discharged the burden. In a case where medical science cannot establish the probability that 'but for' an act of negligence the injury would not have happened but can establish that the contribution of the negligent cause was more than negligible, the 'but for' test is modified, and the claimant will succeed.”

10. To the extent that any waiver seeks exclude or restrict liability for other types of loss (e.g. financial loss), its validity will be subject to the statutory requirement of reasonableness under Section 2(2) the Unfair Contract Terms Act 1977.

11. Volenti non fit injuria operates as a complete defence where the injured party was fully aware of the risks involved with the activity before engaging in it.

12. Under the Law Reform (Contributory Negligence) Act 1945, contributory negligence operates as a partial defence – to apportion liability between the claimant and defendant on the basis of what is fair and reasonable.

13. Various SGBs have implemented, trialled or tabled temporary rule changes aimed specifically at player welfare (e.g. increasing the number of substitutes permitted in football, reducing scrum/contact time in rugby union, the ECB’s decision to play the Test Series against the West Indies in July 2020 at bio-secure venues).