WADA’s Flawed Reporting Limits Regime

Many dozens of prohibited substances are subject to a system requiring them (or their metabolites) to be present in an athlete’s sample at or above certain minimum concentrations in order to constitute a violation of anti-doping rules based on the World Anti-Doping Code (the “Code”). Categories of such substances include stimulants such as cocaine and amphetamine, glucocorticoids, the asthma medication salmeterol, and beta-blockers – most of which are only prohibited in-competition. However, the system applicable to those substances is deeply flawed, and could result in athletes being unfairly charged. This article examines those flaws and describes how they can be remedied.

The relevance of the concentration of certain prohibited substances in athletes’ urine

The Prohibited List of the World Anti-Doping Agency (“WADA”) sets out the substances which, if detected in an athlete’s sample, will result in an adverse analytical finding (i.e. a “positive test”). The caveat to that is that the presence of some of those substances will only result in an adverse analytical finding if present at or above a certain specified concentration. WADA’s categorisation of such substances includes the following:

- “Threshold Substances”, the concentrations of which must be assessed using a specific quantification procedure (“Validated Quantification Procedure”) before determining whether a concentration amounts to an adverse analytical finding, by reference to the applicable Thresholds set out in Technical Document TD2019DL. Such Threshold Substances include natural cannabis, morphine and salbutamol (an asthma medication).

- Substances which fall within Section 4.0 of WADA’s Technical Document – TD2019MRPL (MRPL being an acronym for “Minimum Required Performance Levels”), for which the concentrations are merely estimated before determining whether they amount to an adverse analytical finding, by reference to the applicable reporting limits set out in TD2019MRPL. These substances include stimulants such as cocaine and amphetamine, glucocorticoids such as cortisone, the asthma medication salmeterol, and beta-blockers – most of which are not prohibited in-competition (hereinafter referred to as “Section 4 Substances”). It is the regime associated with these substances which is fraught with problems.

Four fundamental flaws in the Section 4 Substances regime

There are at least four fundamental problems with the manner in which the WADA regime deals with Section 4 Substances.

First, for the purposes of determining whether the concentration of a Section 4 Substance is high enough to amount to an anti-doping rule violation, Anti-Doping Organisations (“ADOs”) rely on the concentration estimates reported by the relevant WADA-accredited laboratories, rather than a Validated Quantification Procedure as used to assess the concentration of Threshold Substances. That is a major problem because concentration estimates are just that – estimates – generated by procedures neither designed nor validated to perform any measurement. Accordingly, such estimates can never be anywhere near as reliable as the results from Validated Quantification Procedures. Thus, an athlete may end up being banned pursuant to a laboratory’s unreliable estimation of a Section 4 Substance concentration, notwithstanding that Validated Quantification Procedures could be developed and used for all Section 4 Substances.

Second, the issue described in the preceding paragraph is exacerbated by the fact that WADA purports to ignore the concentration of a Section 4 Substance in an athletes’ B sample (see paragraph 5.3.4.5.4.8.13 of the WADA International Standard for Laboratories). In other words, WADA expects athletes to simply take as correct the estimated concentration of a Section 4 Substance as reported by the laboratory for their A sample, notwithstanding that the very purpose of B sample analyses is to provide athletes with the opportunity to check the laboratory’s results/workings/methods.

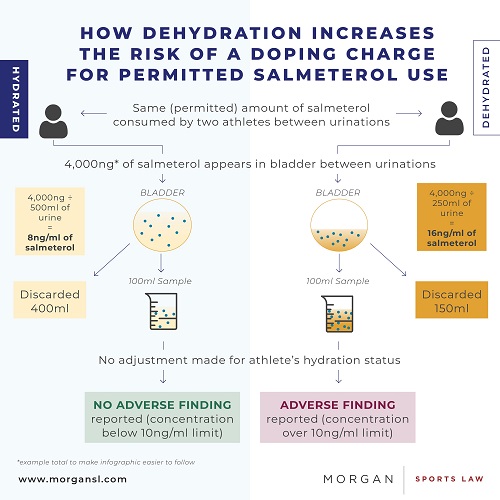

Third, how dehydrated an athlete is (and therefore how concentrated their urine is) will not automatically be taken into account by a laboratory for the purposes of determining whether the applicable reporting limits are exceeded in respect of Section 4 Substances. That is an issue because a dehydrated athlete will have more concentrated urine relative to a well-hydrated athlete, and so the concentration of any substances (prohibited or not) appearing in their urine will be higher, thus increasing the probability of an anti-doping rule violation being pursued against them – simply because of their hydration status. The issue is even more egregious given that the concentration of a urine sample is always measured by the testing laboratory, and the adjustment calculation is very simple. This is not usually a problem for Threshold Substances (at least not now – see below for historical injustices relating to Threshold Substances), as an adjustment is made, as set out in Technical Document – TD2019DL, in order to avoid the risk of “false positives” arising from an athlete’s hydration status. This issue is summarised in the infographic below:

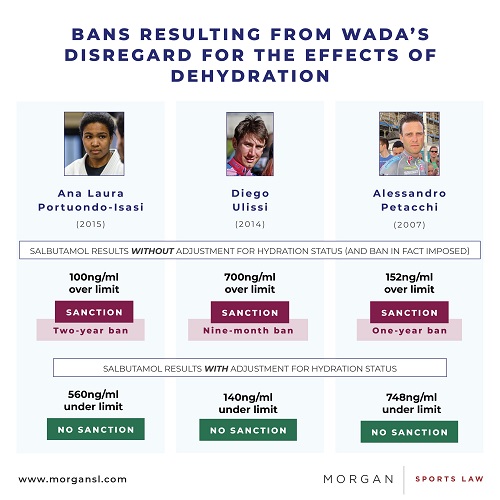

This problem regarding an athlete’s hydration status in respect of Section 4 Substances is perhaps not surprising, however, given the history of how WADA has dealt (or rather not dealt) with it in respect of other types of substances. Taking for example the Threshold Substance salbutamol (an asthma medication), the current Threshold Substance regime has – since March 2018 – allowed for an adjustment to be made according to an athlete’s hydration status, in an attempt to avoid the reporting of “false positives”. However, prior to March 2018, the Threshold Substances regime did not allow for such an adjustment to be made, and consequently several athletes were banned when they should not have been (and would not have been, had the adjustment in question been made to their laboratory results). Examples of such athletes are set out in the following infographic:

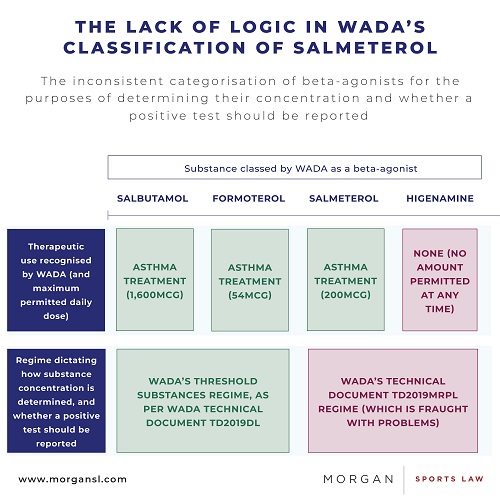

Fourth, WADA’s categorisation of certain substances as a Threshold Substance or Section 4 Substance displays a clear lack of logic. Take, for example, the following substances which WADA has classified as “beta-agonists”: salbutamol, formoterol, salmeterol and higenamine. As asthma medications, salbutamol and formoterol are permitted to be taken below certain specified doses and therefore are classed as Threshold Substances. Salmeterol, on the other hand, while also an asthma medication permitted below a certain specified dose, is classified as a Section 4 Substance – in the same way as higenamine, which is banned at all times. Thus, asthma-suffering athletes who have for some reason been prescribed salmeterol over salbutamol/formoterol (e.g. because they respond better to the former) are discriminated against, in that the flawed Section 4 Substance regime is being imposed on them, and they are treated in the same way as users of higenamine, which is (currently) banned at all times. The issue is summarised in the infographic below:

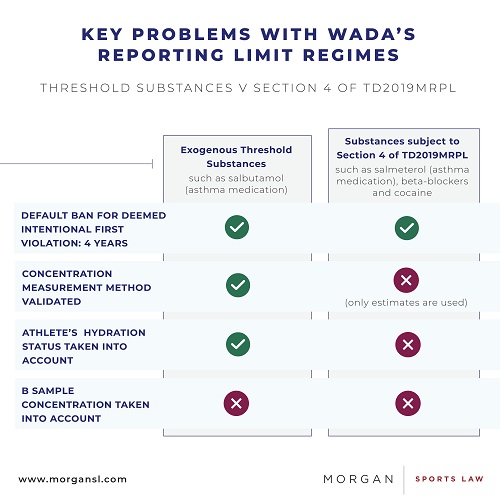

The most significant issues described above can be summarised by the infographic below:

In short, WADA’s Section 4 Substance regime is fundamentally flawed, and could result in manifest injustices being committed against athletes.

The position described above is unacceptable, and becomes even more so when it is considered that WADA is aware of at least some the problems described. See for example the comment to Article 3.2.1 of the 2021 WADA Code, which states that “[i]n no event shall the possibility that the exact concentration of the Prohibited Substance in the Sample may be below the Minimum Reporting Level constitute a defense to an anti-doping rule violation”. Given the severe repercussions for an anti-doping rule violation, there is no excuse for WADA maintaining such a flawed and unfair system, which is founded on a disregard for basic scientific principles and plain logic.

How the flaws might be resolved

The issues described above can be resolved in a simple and fair manner. All that WADA has to do is (a) reclassify the Section 4 Substances as Threshold Substances (or otherwise treat them the same), and (b) allow the concentration of the relevant substance in the B sample to be calculated and taken into account to determine whether an anti-doping rule violation should be pursued. While doing so will inevitably increase a laboratory’s costs, such increase would be a small price to pay, given that the alternative is the wrongful charging of athletes based on unreliable laboratory reports issued pursuant to the flawed Section 4 Substances regime.

Authored by

Richard Martin

Partner

Ihar Nekrashevich

Science Analyst

Sam Comb

Science Analyst