Competency of National Dispute Resolution Chambers

1. Introduction

The precise forum in which a football dispute should be decided at first instance – whether a civil court, a domestic employment tribunal, an arbitral panel established by a national federation, or a FIFA decision-making body – may not always be obvious. Whilst arbitration is recognised as the principal mechanism for resolving football disputes – something that is enshrined within FIFA’s Statutes– the appropriate jurisdiction will largely depend on the nature of the dispute (though the characterisation of a dispute can, in itself, sometimes be a source of disagreement).

It is not unusual for parties to challenge the particular forum in which a claim is commenced – for instance, where the forum is deemed to lack competency (such that it could create concerns around the ultimate enforcement of an award), or for tactical reasons (e.g. if an alternative forum is deemed to have more a favourable procedural law, greater/lesser sanctioning powers, etc.).

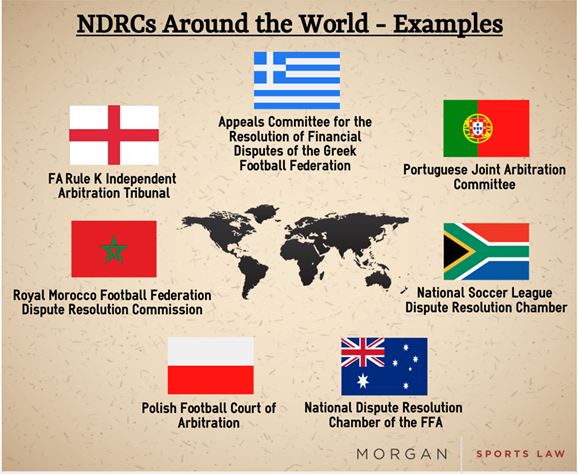

An ever-increasing number of national football federations have implemented their own mechanisms for resolving football disputes, through the creation of (so-called) national dispute resolution chambers (“NDRCs”). In this article, Henry Goldschmidt (Associate) examines the competency of NDRCs to deal with player-club employment disputes of an international dimension – a matter that has habitually reared its head before FIFA and the Court of Arbitration for Sport (“CAS”) in recent years.

2. FIFA Regulations on the Status and Transfer of Players

2. FIFA Regulations on the Status and Transfer of Players

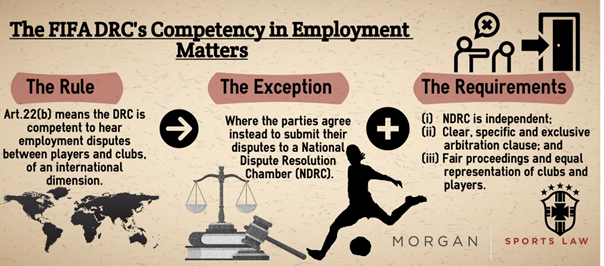

Article 22(b) of the FIFA Regulations on the Status and Transfer of Players (“FIFA RSTP”)provides as follows:

Without prejudice to the right of any player or club to seek redress before a civil court for employment-related disputes, FIFA is competent to hear:

[…]

b) employment-related disputes between a club and a player of an international dimension; the aforementioned parties may, however, explicitly opt in writing for such disputes to be decided by an independent arbitration tribunal that has been established at national level within the framework of the association and/or a collective bargaining agreement. Any such arbitration clause must be included either directly in the contract or in a collective bargaining agreement applicable on the parties. The independent national arbitration tribunal must guarantee fair proceedings and respect the principle of equal representation of players and clubs;

(Emphasis added)

Specifically, in accordance with Article 24(1) of the RSTP,it should be FIFA’s Dispute Resolution Chamber (the “FIFA DRC”) that shall adjudicate cases that fall within Article 22(b).However, as set out above, Article 22(b) of the FIFA RSTP allows for such cases to resolved by an “independent arbitration tribunal that has been established at national level within the framework of the association and/or a collective bargaining agreement” (i.e. an NDRC) to determine player-club employment disputes of an “international dimension”.

3. International (or national) dimension?

3. International (or national) dimension?

What constitutes “international” in the context of Article 22(b) has been the subject of debate – but the consensus is that it is based on the national status of the parties to the dispute, rather than the national status of the dispute itself. According to the Panel in CAS 2016/A/4846, this is the “common sense” interpretation. In addition, the FIFA RSTP Commentary to Article 22(b) provides that the “international dimension is represented by the fact that the player concerned is a foreigner in the country concerned”.

Incidentally, where a player-club employment dispute is not of an international dimension and the contract is silent as to the jurisdiction:

(1) the statutes/regulations of an NDRC would usually provide that the NDRC is competent to deal with disputes where each party is subject to the national association’s jurisdiction (i.e. when the parties are (i) a club affiliated to the national association; and (ii) a player registered to that club);

(2) if there is no NDRC in place for a national association, or the player-club employment dispute falls outside its competence (e.g. if the player has not been formally registered with the club), the parties would need to seek recourse via an ordinary court.

The FIFA DRC cannot determine disputes that fall outside Article 22 of the FIFA RSTP and will thus never be competent to deal with a dispute of a (purely) national dimension, irrespective of what the parties agree amongst themselves.

4. Competency requirements for an NDRC

The mandatory criteria

Assuming the “international” element is satisfied, the following requirements must be met for an NDRC to be considered competent to determine player-club employment disputes:

(1) the NDRC is independent;

(2) the exclusive jurisdiction of the NDRC derives from clear and specific reference in the player’s employment contract;

(3) the NDRC chosen by the parties guarantees fair proceedings and respects the principle of equal representation of clubs and players.

A party that disputes FIFA’s jurisdiction to determine a claim under Article 22(b) of the FIFA RSTP – or that otherwise claims that an NDRC has jurisdiction over the matter – bears the burden of establishing that the NDRC has jurisdiction over the dispute.

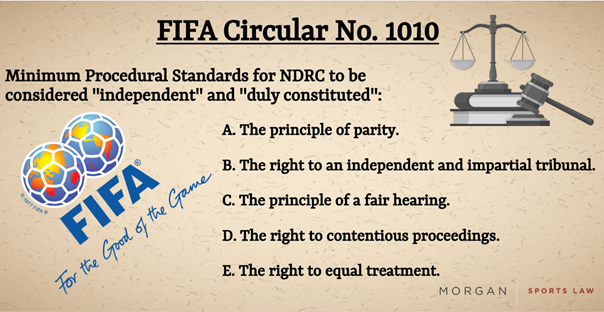

FIFA Circular No. 1010

In its Circular No. 1010 (dated 20 December 2005), FIFA clarified the minimum (international) procedural standards an arbitral tribunal must uphold in order to be classed as “independent” and “duly constituted” – namely: (a) the principle of parity when constituting the arbitration tribunal, (b) the right to an independent and impartial tribunal, (c) the principle of a fair hearing, (d) the right to contentious proceedings, and (e) the right to equal treatment.

These five conditions have effectively become the yardstick with which NDRCs must comply in order to oust the jurisdiction of the FIFA DRC. Indeed, the above principles are regularly cited in awards where the competency of an NDRC is under scrutiny.

FIFA’s NDRC Standard Regulations

FIFA’s NDRC Standard Regulations

In addition to the above, FIFA’s NDRC Standard Regulations (“NDRC Regulations”) were implemented by FIFA Circular No. 1129 (dated 28 December 2007) as guidelines for Member Associations for establishing a national dispute resolution system. The NDRC Regulations – effective from 1 January 2008 – reflected the principles of the FIFA DRC and provide that the “NDRC shall apply the association’s statutes and regulations, in particular those adopted on the basis of the FIFA Statutes and regulations.”

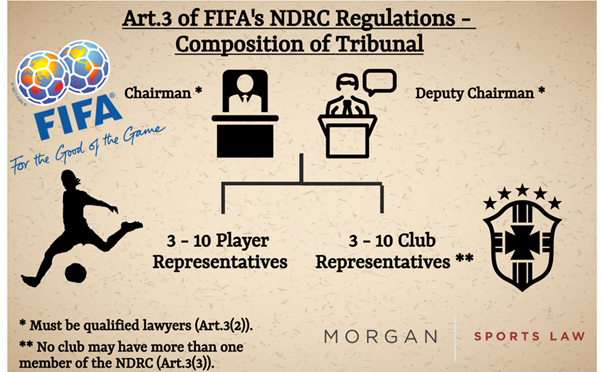

The majority of cases where NDRCs are deemed to fall short (see below) of the prescribed independence and/or fairness mandate relate to the composition of the panel – something that is addressed in Article 3 of the NDRC Regulations:

Article 3 – Composition

1. The NDRC shall be composed of the following members, who shall serve a four-year renewable mandate:

a) A chairman and a deputy chairman chosen by consensus by the player and club representatives from a list of at least five persons drawn up by the association’s executive committee;

b) Between three and ten player representatives who are elected or appointed either on the proposal of the players’ associations affiliated to FIFPro, or, where no such associations exist, on the basis of a selection process agreed by FIFA and FIFPro;

c) Between three and ten club representatives who are elected or appointed on the proposal of the clubs or leagues.

2. The chairman and deputy chairman of the NDRC shall be qualified lawyers.

3. No club may have more than one member of the NDRC.

5. Recent CAS jurisprudence

5. Recent CAS jurisprudence

Article 59 of FIFA’s Statutes serves to recognise the CAS as the international ‘supreme court’ of football. FIFA has recognised the CAS since 2002 as the appeal body for decisions from the FIFA DRC (and the FIFA Players’ Status Committee). Below are examples of how the CAS has applied the rules, regulations and competency standards relating to NDRCs.

Arbitration clause/agreement insufficient to confer jurisdiction on an NDRC

As outlined above, it must be clear – from express reference in a player’s employment contract – that the chosen NDRC has exclusive jurisdiction over any dispute between the player and the club. This requirement was affirmed by the Panel in CAS 2015/A/4333, which held that an arbitration clause “has to designate a particular arbitral tribunal or at least an arbitral tribunal that is determinable by contractual interpretation” – something that the parties had failed to do in the underlying employment contract.

In CAS 2014/A/3864, the CAS considered whether two Romanian national arbitral bodies had jurisdiction to decide a dispute emanating from a Sporting Services Agreement (the “Agreement”) and Contract of Employment (the “Contract”) between a Portuguese player and Romanian club. In that instance, the Sole Arbitrator held that the relevant dispute resolution clauses of the Agreement and the Contract referenced multiple fora (including a specific reference to FIFA), as purportedly capable of resolving contractual disputes – without explicitly determining one that would be competent, to the exclusion of others.

See also CAS 2014/A/3684 & 3693, where the Panel concluded that the standards of Article 22(b) of the RSTP were not met as the relevant employment contract did not contain any explicit reference to the competence of the Portuguese Joint Arbitration Committee (the “Portuguese NDRC”) or the applicable articles in the Portuguese Collection Bargaining Agreement.

NDRCs held to have lacked independence/fairness

As indicated above, the most frequent ground on which an NDRC is found not to have competency is on the basis of its composition – for instance, in CAS 2016/A/4846. In that case, although it was undisputed that the relevant employment contract contained a clear dispute resolution clause in favour of the National Soccer League Dispute Resolution Chamber (the “South African NDRC”), the Panel determined that the South African NDRC did not respect the mandated principle of equal representation of players and clubs as:

(1) the South African NDRC Executive Committee was comprised of the chairperson of the National Soccer League South Africa (the “League”), seven additional persons elected by the clubs and the Chief Executive Officer of the League; and

(2) in addition, the South African NDRC did not comply with Article 3(1) of the NDRC Regulations, as the chairperson of the South African NDRC was appointed by the Executive Committee of the League and not by consensus of player and club representation.

In CAS 2014/A/3690, the Panel found that the Appellant (a Polish club) was unable to provide evidence that clubs and players were able to exercise equal influence over the compilation the arbitrators’ list of the Polish Football Court of Arbitration (the “Polish NDRC”). In deciding that the Polish NDRC lacked the requisite “independence”, the Panel held:

Article 11 para. 1 of the Polish FA’s Resolution II/25 states that the [Polish NDRC] is “composed from 25 to 27 arbiters appointed by the Management Board of the Polish Football Association”. As a result, given the clubs are direct members of the Polish FA (and can thus influence the composition of the Management Board) while the players are not, the Panel holds that such national arbitral tribunal cannot be considered as duly constituted pursuant to FIFA requirements and, thus, cannot be deemed as having jurisdiction to hear the present dispute.

In CAS 2018/A/5659(an award rendered in March 2019 that is, as yet, unpublished), the Panel (interestingly) did not come to a definitive conclusion as to whether the relevant arbitration clause expressly and clearly conferred exclusive jurisdiction on the relevant NDRC. Instead, it was held that this could be “left open” on the basis that the NDRC was not deemed to respect the principle of equal representation of player and clubs – i.e. it lacked the requisite competency in any event.

In coming to that decision, although the Panel did not suggest that the proceedings before the NDRC were unfair or lacked the desired quality, it was considered that:

(1) the sole fact that the president and vice-president of a panel are selected by the Board of Directors of the national federation raised doubts about their neutrality – particularly given that decisions of the NDRC are decided by a majority and the president has a casting vote;

(2) conversely, the players’ group did not seem to be able to exercise equal influence over the selection process and the composition of the arbitrators’ list (from which the president and vice-president were selected);

(3) as such, the appointment of the president was not in line with the minimum expectations of FIFA.

No recognition in the abstract

As indicated above, the burden of proof will be on the party challenging FIFA’s jurisdiction to determine an Article 22(b) dispute. Further, there will be no recognition by the CAS in the abstract – in other words, analysis of an NDRC’s competence will be based on the particular context of the dispute at hand and the evidence/submissions of the parties.

A clear example of this approach is evidenced in CAS 2014/A/3656, when the Panel felt the Appellant Club did not provide sufficient evidence to demonstrate that the Appeals Committee for the Resolution of Financial Disputes of the Greek Football Federation (the “Greek NDRC”) was an independent arbitral tribunal guaranteeing fair proceedings and equal player/club representation. This was notwithstanding that, two years prior, the CAS had held that the same Greek NDRC met the requirements to be competent in lieu of the FIFA DRC.

Whilst the Panel in CAS 2014/A/3656 considered (and duly referenced) the earlier decision, it did not consider itself to be in a position to reach the same conclusion:

… the Panel finds that based on the evidence at its disposal and because the Club did not duly inform the Player of the pending proceedings instigated against him by the Club before the [Greek NDRC]… it must be assumed, in the absence of proof to the contrary, that these principles were not complied with by the [Greek NDRC] in the present case. Under such circumstances, the duty of the [Greek NDRC] to guarantee fair proceedings and equal representation cannot be assessed in the abstract, since doing so would require the Panel to ignore and disregard the fact that in this case the Player was not duly informed of the pending proceedings and will contradict the intention of Article 22(b) of the FIFA [RSTP].

(Emphasis added)

6. Comment

When it comes to determining the appropriate jurisdiction of a player-club employment dispute of an international nature, the starting point should always be the contract itself – being what the parties agreed in writing. It is apparent from recent CAS jurisprudence that the parties will need to expressly and clearly agree that the relevant NDRC has exclusive jurisdiction, if they wish to oust the FIFA DRC (i.e. “opt out” of the status quo).

If that initial limb is satisfied, there are then very strict checks and balances that an NDRC must have in place to be deemed “competent” to decide a player-club employment dispute of an international dimension. Whilst different parts of the world may have different understandings as to what constitutes judicial “independence”, the NDRC Regulations provide for a standardised framework of minimum standards expected of an NDRC.

It is evident from CAS jurisprudence that NDRCs are often held to have infringed the “principle of equal representation of clubs and players” – generally because the make-up of the NDRCs is disproportionately influenced by clubs. As such, particular attention should be paid to Article 3(1) of the NDRC Regulations, to ensure:

(1) parity with respect to the interests of clubs and players; and

(2) balance with respect to the composition of the NDRCs.

Finally, the fact that no assessment will be made in the abstract should serve as a warning against any complacency on the part of a party seeking to challenge the jurisdiction of FIFA. Indeed, one should never assume that, just because a particular NDRC has been deemed “competent” in the past, that it will again in future. The jurisdiction of any given NDRC will be assessed in the context of the particular dispute, so it will be essential for the party disputing FIFA’s jurisdiction (and seeking to invoke the jurisdiction of an NDRC) to develop and corroborate its arguments on the issue as far as possible.

Footnote

1. See: (1) Article 57-59 of FIFA’s Statutes. Note, Article 59 of FIFA’s Statutes precludes (save in very limited circumstances) recourse to ordinary civil courts and dictates that national associations ensure disputes are resolved by way of arbitration. (2) Article 15(f) of FIFA’s Statues, in relation of member associations’ statutes, which provides that “all relevant stakeholders must agree to recognise the jurisdiction and authority of CAS and give priority to arbitration as a means of dispute resolution.”

2. The FIFA RSTP were approved by the FIFA Council on 27 October 2017 and came into force on 1 January 2018. The FIFA RSTP were subsequently amended by FIFA Circular Letter No. 1625 (dated 26 April 2018) and FIFA Circular Letter No. 1679 (dated 1 July 2019).

3. Article 24(1) of the RSTP states that: “[t]he Dispute Resolution Chamber (DRC) shall adjudicate on any of the cases described under article 22 a), b), d) and e) with the exception of disputes concerning the issue of an [International Transfer Certificate].”

4. The development and competences of the FIFA DRC are examined by Mario Flores Chemor (Associate, Morgan Sports Law) in his article dated 22 July 2019.

5. For instance, see: (1) CAS 2016/A/4846 Amaaazulu FC v. Jacob Pinehas Nambandi & FIFA & National Soccer League South Africa, at paras. 144-152 of the Award dated 13 September 2017. In that case, the “Panel has no doubt that the Player, being a Namibian national without a South African passport is a foreigner in South Africa. The Panel finds that a clear distinction must be made between having a residence permit (which the Player has) and being a citizen of the country concerned (which the Player is not).” It therefore rejected the League’s argument that the domicile of the Player is decisive and held that the “mere fact that the Player agreed that he would be registered as a South African in the Employment Contract does not make this any different.” (2) CAS 2014/A/3682 Lamontville Golden Arrows Football FC v. Kurt Kowarz & FIFA, at para. 59 of the Award dated 14 July 2015. Although that case related to a coach-club (rather than player-club) employment dispute, it clarifies why the “international” element is defined by the nationality of the parties. The Panel held that the international dimension is represented by the fact the German Coach is a foreigner in the county concerned (South Africa) and that “to find otherwise would undermine the entire rationale of the FIFA PSC affording to itself jurisdiction, and affording protection to the parties, in employment contracts involving foreign nationals.” Note, under Articles 22(c) and 23(1) of the FIFA RSTP, the FIFA PSC (rather than the FIFA DRC) has jurisdiction over coach-club disputes of an international dimension, subject to certain caveats.

6. CAS 2016/A/4846 Amaaazulu FC v. Jacob Pinehas Nambandi & FIFA & National Soccer League South Africa, at para. 144 of the Award dated 13 September 2017: “common sense leads to this conclusion, for if the national status of the dispute and not of the parties were to be decisive, employment-related disputes in football could hardly have an international dimension because employment contracts in football are usually concluded and enforced in the country of the club and are therefore governed by the rules and regulations of the national association concerned and do not have any international dimension.

7. As set out in Article 5(1) of the FIFA RSTP, “a player must be registered at an association to play for a club as either a professional or an amateur [and] only registered players are eligible to participate in organised football.” However, the validity of a contract between a player and club is not conditional upon the formal registration of the player (such registration being the new club’s sole responsibility). For instance, in FIFA DRC Decision No. 814573 (at para. 3 of the facts) dated 20 August 2014, the FIFA DRC disregarded a clause which attempted to make the validity of the contract subject to the player’s registration. Sometimes, due to administrative errors or the requisite documentation/information not being uploaded to FIFA TMS in time (for instance, if a deal is completed close to the transfer window deadline), a player can be employed by a club but remain unregistered (i.e. unable to play). Where a player is unregistered with a member association, the player cannot be subject to the jurisdiction of the NDRC – for example, see (i) FIFA DRC Decision No. 8132676 (at para. 7 of the considerations) dated 30 August 2013, and (ii) FIFA DRC Decision No. 4150167 (at para. 8 of the considerations) dated 24 April 2015. Interestingly, for player-club employment disputes of an international dimension, the position is different – as the FIFA DRC will assume jurisdiction regardless of whether a player is registered or not.

8. See FIFA DRC Decision No. 1016908 dated 13 October 2016. If a player holds dual nationality, the matter is less straightforward.

9. For example, see: (1) CAS 2014/A/3684 Leandro da Silva v. Sport Lisboa e Benfica & CAS 2014/A/3693 Sport Lisboa e Benfica v. Leandro da Silva, at para. 60 of Award dated 16 September 2015. (2) CAS 2008/\A/1518 Ionikos FC v. L, at paras. 29-31 of the Award dated 23 February 2009.

10. For example, see: (1) CAS 2016/A/4846 Amaaazulu FC v. Jacob Pinehas Nambandi & FIFA & National Soccer League South Africa, at para. 166 of the Award dated 13 September 2017: “It remained undisputed between the parties that the burden of proof was on the Club to establish that the South African NDRC complied with FIFA’s requirements.” (1) FIFA DRC Decision No. 6132540 dated 7 June 2013, at para. 12. In that case, “the Respondent did not provide any documentary evidence in support of its arguments. As a consequence, the Respondent was unable to prove that [the NDRC] meets the minimum procedural standards for independent tribunals”.

11. FIFA Circular No. 1010 clarified the terms “independent” and “duly constituted” in accordance with Article 60, para. 3(c) of the FIFA Statues (2005 edition) applicable at the time – a provision addressing the jurisdiction of the CAS.

12. The parties must have equal influence over the appointment of arbitrators. This means for example that every party shall have the right to appoint an arbitrator and the two appointed arbitrators appoint the chairman of the arbitration tribunal. The parties concerned may also agree to appoint jointly one single arbitrator. Where arbitrators are to be selected from a predetermined list, every interest group that is represented must be able to exercise equal influence over the compilation of the arbitrator list.

13. To observe this right, arbitrators (or the arbitration tribunal) must be rejected if there is any legitimate doubt about their independence. The option to reject an arbitrator also requires that the ensuing rejection and replacement procedure be regulated by agreement, rules of arbitration or state rules of procedure.

14. Each party must be granted the right to speak on all facts essential to the ruling, represent its legal points of view, file relevant motions to take evidence and participate in the proceedings. Every party has the right to be represented by a lawyer or other expert.

15. Each party must be entitled to examine and comment on the allegations filed by the other party and attempt to rebut and disprove them with its own allegations and evidence.

16. The arbitration tribunal must ensure that the parties are treated equally. Equal treatment requires that identical issues are always dealt with in the same way vis-à-vis the parties.

17. For example, see: (1) CAS 2016/A/4846 Amaaazulu FC v. Jacob Pinehas Nambandi & FIFA & National Soccer League South Africa, at para. 157 of the Award dated 13 September 2017. (2) CAS 2014/A/3656 Olympiakos Volou FC v. Carlos Augusto Bertoldi, at para. 184 of the Award dated 17 November 2015. (3) CAS 2012/A/2983 ARIS Football Club v. Márcio Amoroso dos Santos & FIFA, at para. 8.6 of the Award dated 22 July 2013.

18. Article 2 of the FIFA’s NDRC Standard Regulations.

19. Football and the Law, Nick De Marco QC, 2018 (First Edition), para 28.3. As the ‘supreme court’, the CAS “has a central role in the development of the law relating to football and seeking to ensure consistency of approach across the worldwide game” (para. 28.107).

20. FIFA Circular No. 827 dated 10 December 2002.

21. CAS 2015/A/4333 MKS Cracovia SSA v. Bojan Puzigaca & FIFA, Award dated 10 April 2017.

22. Ibid., para. 69 of the Award.

23. CAS 2014/A/3864 AFC Astra v. Laionel da Silva Ramalho & FIFA, Award dated 31 July 2015.

24. Ibid., paras.70-72 of the Award.

25. CAS 2014/A/3684 Leandro da Silva v. Sport Lisboa e Benfica & CAS 2014/A/3693 Sport Lisboa e Benfica v. Leandro da Silva, Award dated 16 September 2015.

26. Ibid., see paras. 56-63 of the Award. Sport Lisboa e Benfica (the Portuguese Club) believed that the employment contract with Leandro da Silva (the Brazilian Player) contained a clear arbitration clause, rendering the Portuguese Joint Arbitration Committee (the “Portuguese NDRC”) competent in the dispute under Article 22(b) of the FIFA RSTP. Indeed, Clause 17 of the employment contract stated that “the cases and situations that are not in this contract are subject to CTT Regulation”. The Club argued that this rendered applicable Article 54 of the CTT Regulation (the Portuguese Collective Bargaining Agreement, the “CBA”), namely that “in case of a dispute arising from this contract of employment, it shall be submitted to the [Portuguese NDRC]”. Nevertheless, the Panel felt that Clause 17 of the employment contract did not explicitly reference the Portuguese NDRC’s competence or the applicable articles of the CBA. The Panel further noted Article 9 of Annex II of the CBA, which stipulates that “for the purpose of art. 3 lit. c of Annex II (which provides that the Portuguese NDRC is competent to hear sports employment-related disputes), the competence of the JAC depends on the arbitration cause”.

27. CAS 2016/A/4846 Amaaazulu FC v. Jacob Pinehas Nambandi & FIFA & National Soccer League South Africa, Award dated 13 September 2017.

28. Ibid., at paras. 160-163 of the Award dated 13 September 2017.

29. CAS 2014/A/3690 Wisla Kraków S.A. v. Tsvetan Genkov, Award dated 16 September 2015.

30. Ibid., at para. 108 of the Award.

31. CAS 2018/A/5659 Al Sharjah Football Club v. Leonardo Lima da Silva & FIFA, Award dated 29 March 2019.

32. In that instance, the Appellant also failed to show that the appeal procedure met FIFA’s prescribed standards.

33. Ibid., paras. 53 and 57 of the Award.

34. For example, see CAS 2014/A/3690 Wisla Kraków S.A. v. Tsvetan Genkov, at para. 108 of the Award dated 16 September 2015.

35. CAS 2014/A/3656 Olympiakos Volou FC v. Carlos Augusto Bertoldi, Award dated 17 November 2015.

36. CAS 2012/A/2983 ARIS Football Club v. Márcio Amoroso dos Santos & FIFA, Award dated 22 July 2013.

37. CAS 2014/A/3656 Olympiakos Volou FC v. Carlos Augusto Bertoldi, at para. 199 of the Award dated 17 November 2015.