Horse Spiking: what does it take to prove it?

A recent decision by the British Horseracing Authority (“BHA”) Disciplinary Panel to impose ten-year bans on two men shows that spiking in sport – and in horses – does happen.

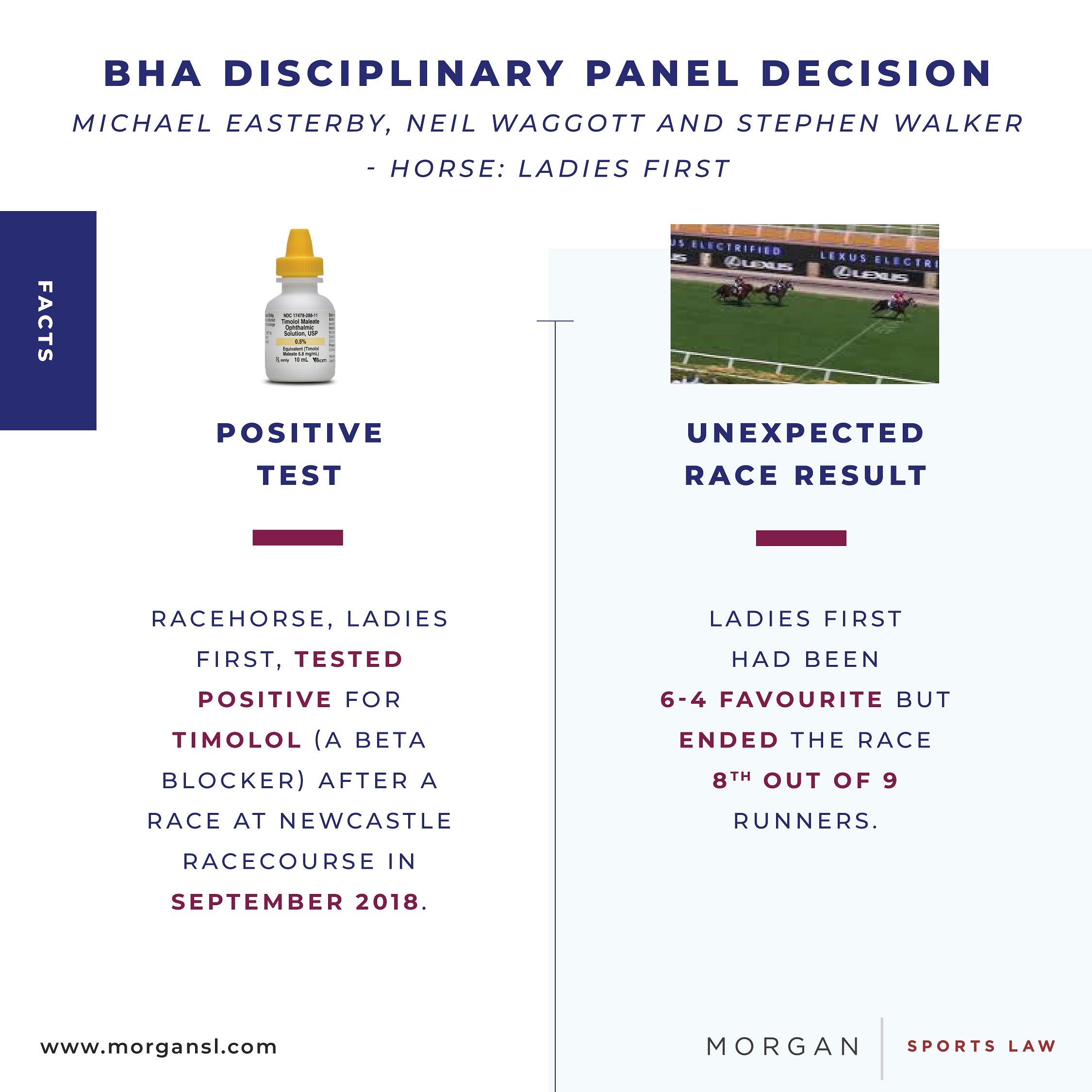

The case arose out of a positive test recorded by the horse LADIES FIRST following a race in September 2018. LADIES FIRST tested positive for the prohibited substance Timolol, a beta blocker.

The two men, who worked at Newcastle Racecourse, had gained access to the stables and proceeded to administer Timolol to LADIES FIRST (the 6-4 favourite). Timolol is known to stop horses mid-race and the Panel determined that the two men had maliciously administered Timolol to LADIES FIRST to adversely affect her race (she finished eighth of nine runners). The two men also approached another horse, VICTORIANO, who was not tested on the day but whose hair subsequently tested positive for traces of Timolol.

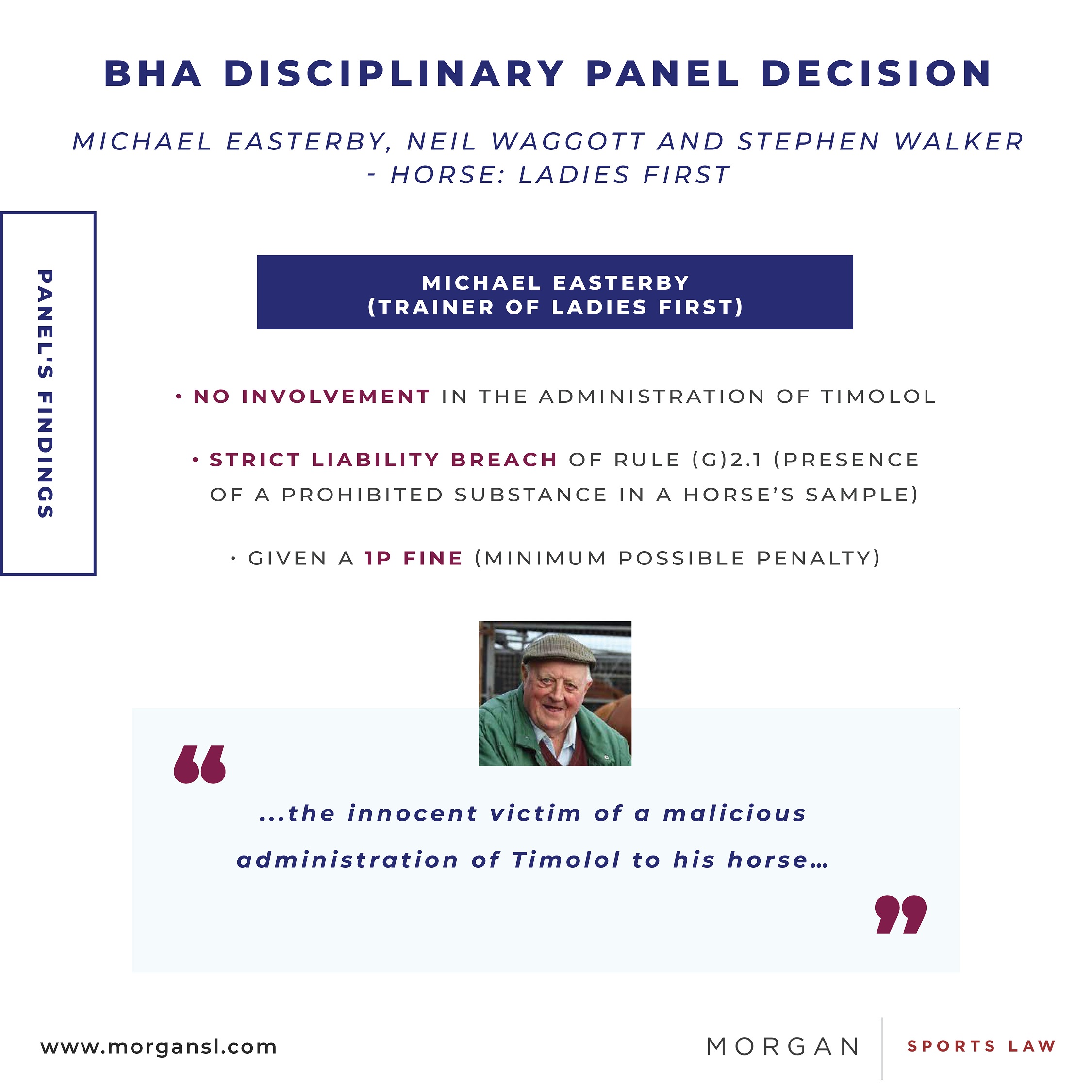

Unsurprisingly in the circumstances, LADIES FIRST’s trainer, Mick Easterby (who had no link to the two men), was found to bear no fault for the positive test.

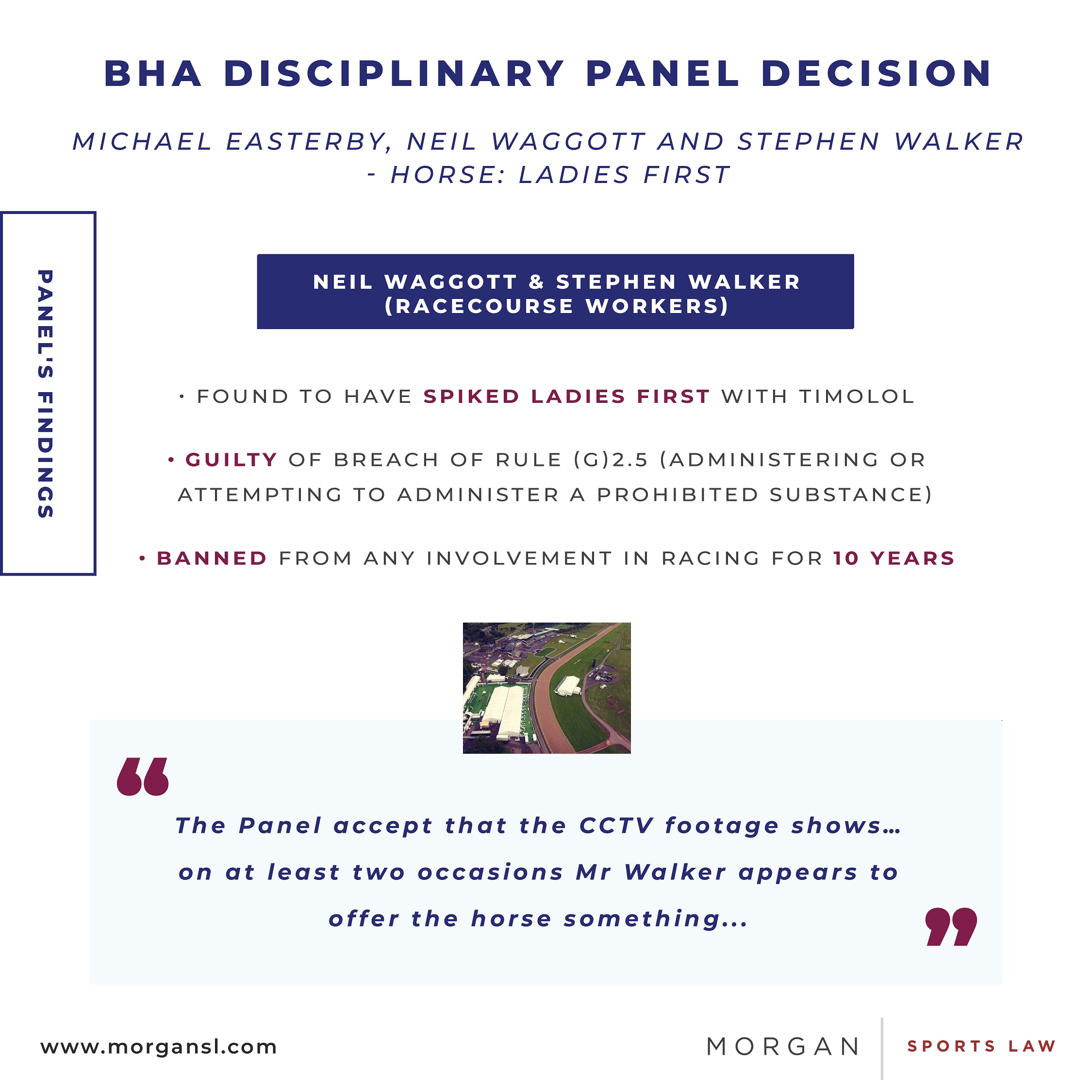

The incident is significant because, had the two men not been caught on CCTV footage appearing to feed LADIES FIRST, claims of spiking may have fallen on deaf ears and the horse’s trainer may not have been able to clear his name.

Following this case, this article explains why anti-doping authorities should not be as quick as they usually are to dismiss spiking claims and asks whether it is time to consider mandating CCTV in protected areas, such as stables, at high-profile equine events.

Why is spiking so difficult to prove?

If a trainer (or other Responsible Person) is accused of an equine anti-doping rule violation and claims that their horse was spiked, many people may jump to the conclusion that this is simply an attempt to cover up intentional doping. That is not particularly surprising, given that spiking is an explanation that has been provided many times in anti-doping cases, but has rarely been proven.

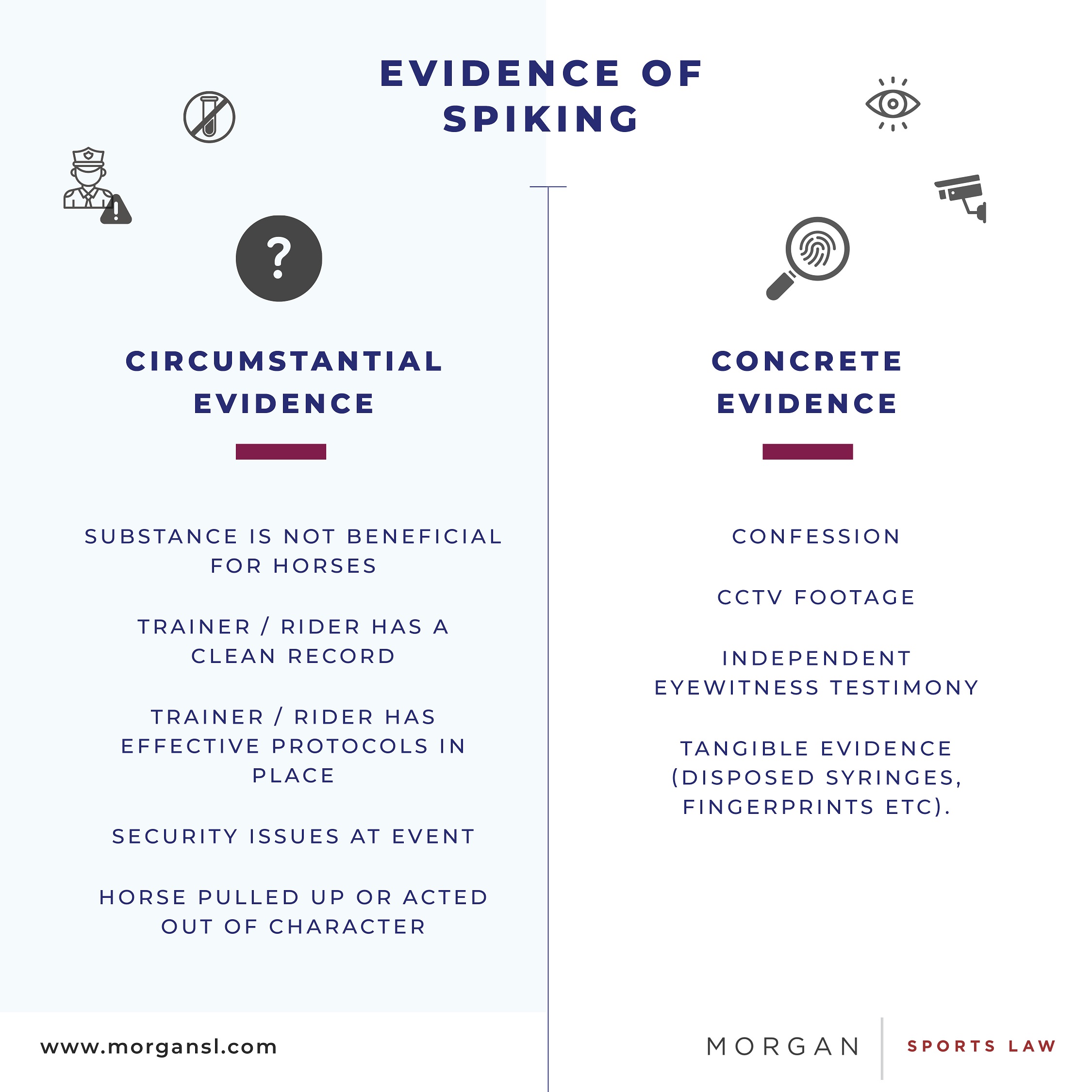

However, when considering the failed defences, it must be remembered that spiking will typically be difficult to establish since it is, by its very nature, a furtive activity. In the absence of video footage, compelling eyewitness testimony or a confession, trainers and other Responsible Persons may have to base their case on circumstantial evidence which, at first glance, may appear underwhelming.

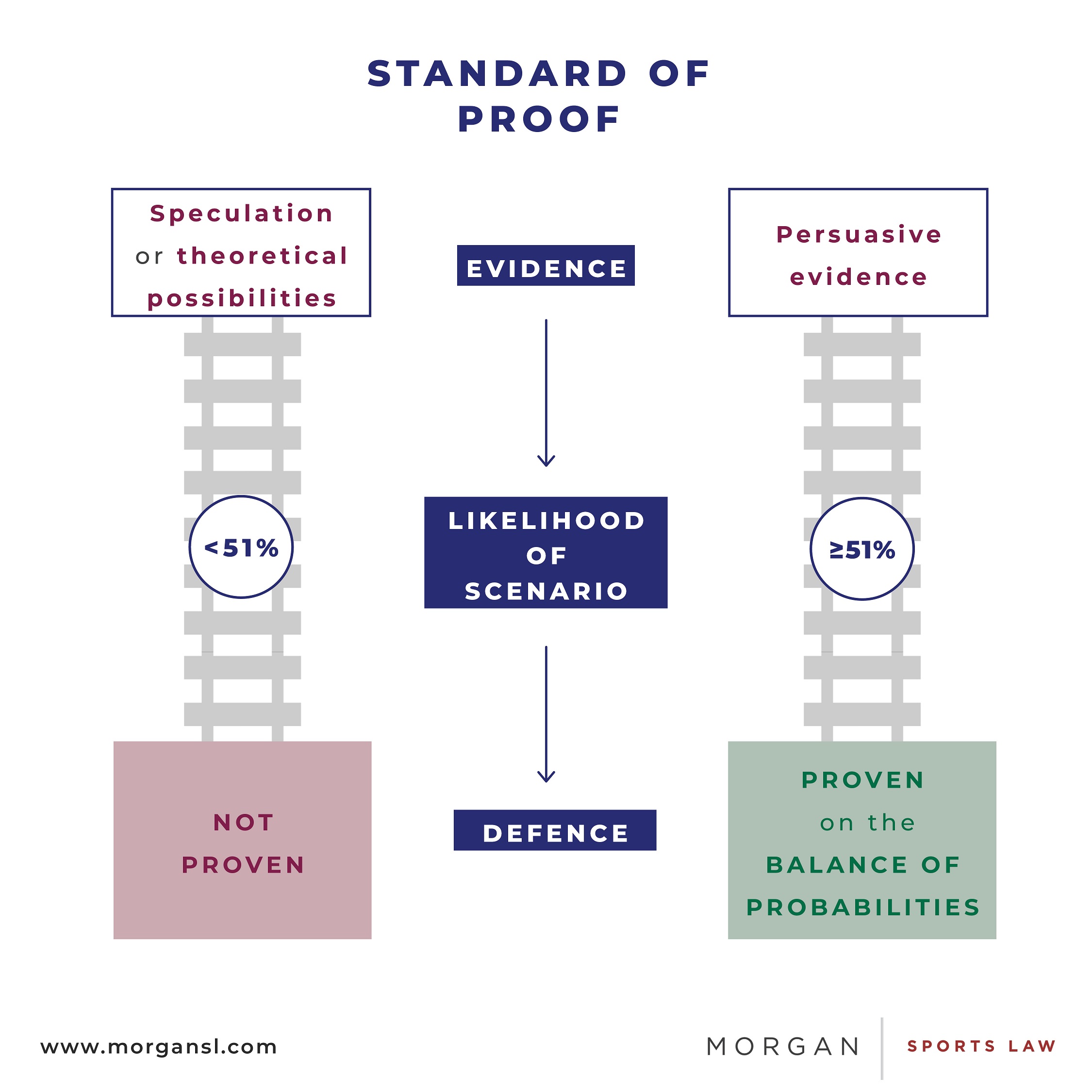

In at least the vast majority of anti-doping cases, including equine anti-doping cases before the Fédération Equestre Internationale (“FEI”) Tribunal and appeals to the Court of Arbitration for Sport, an athlete will be required to prove their defence on the “balance of probabilities”.

This means that a trainer, rider or other Responsible Person will have to prove that their explanation for the positive test (e.g. spiking) is “more likely than not” to have occurred. This is lower than the standard of proof in the English criminal courts – which is “beyond reasonable doubt” – but it still requires the defendant to do more than merely raise “speculation or theoretical possibilities”.

From the decision in the case of LADIES FIRST, it is clear that there was both circumstantial and concrete evidence that spiking had occurred.

As to the circumstantial evidence, there were concerns about security measures at Newcastle Racecourse – the two men should not have had access to the stabling area and there was no evidence that they had been subject to suitability or security checks before they started working at the racecourse. In addition, BHA investigators had inspected Mr Easterby’s yard (unannounced) several weeks after the positive test and found no products containing Timolol, had no complaints about how the yard was run, and collected samples from all three horses under his control, none of which subsequently tested positive for any prohibited substances.

However, whilst those circumstances would clearly support a defence of spiking, in the absence of additional evidence it would have been understandable if the Panel had concluded that Mr Easterby had not established on the balance of probabilities that LADIES FIRST had indeed been spiked. It was therefore incredibly fortunate that the spiking incident was captured on CCTV.

Spiking having been established, the two men were found guilty of breaching Rule (G)2.5 (administering or attempting to administer a Prohibited Substance) and given the longest possible ban (10 years).

Regarding Mr Easterby, the Panel found that he “was the innocent victim of a malicious administration of Timolol to his horse”. However, the BHA Equine Anti-Doping Rules (like most anti-doping rules) impose a ‘strict liability’ standard, whereby the trainer, or other Responsible Person, commits a violation whenever a prohibited substance is present in their horse’s system, regardless of whether there was any intent, fault, negligence or knowing use on their part.

Accordingly, Mr Easterby was found to have breached Rule (G)2.1 (presence of a Prohibited Substance in a Horse’s Sample). However, a token fine of only 1p was imposed given Mr Easterby’s lack of fault. The Panel also disqualified LADIES FIRST’s result from the race, as was required by Rule (G)11.2.1.

Going forwards

Unfortunately, in most cases of suspected spiking, there is no CCTV footage. In particular, in the FEI-sanctioned equestrian sports, such as showjumping, dressage and eventing, CCTV is not common. While stables are restricted areas with 24-hour security and sign-in protocols to ensure that only authorised individuals can enter, what those individuals do in the stables is not typically recorded. Riders are permitted to install their own CCTV in the event stables during shows (for the sole purpose of monitoring their horses), but this can be costly, and they have to obtain prior permission from the FEI, which can be administratively burdensome for riders travelling on the show circuit.

Perhaps, therefore, it is time for the FEI to mandate that events install CCTV in and near stables, to deter both spiking and doping (as well as horse abuse and other rule breaches), and to assist investigations if such allegations are subsequently made. Fundamentally, the Newcastle Racecourse incident highlights that spiking does happen – and with the right security measures, it can be proven to have happened.

Authored by

Emma Waters

Associate

Equestrian Services Team

Ellen Kerr

Trainee Solicitor

Equestrian Services Team