Arbitrator diversity at the Court of Arbitration for Sport - Part Two

Part One of this article reported that data from over 2,000 publicly available awards showed that arbitrators appointed in CAS disputes lack diversity as regards both their gender and ethnicity (by reference to skin colour). Part One also explained that, whilst some moderate improvement was achieved between January 2000 and September 2020, progress had been far too slow, and that the CAS lags behind even the underwhelming diversity standards set by other arbitral institutions.

This Part Two explains why arbitrator diversity at CAS matters and provides suggestions as to what the CAS and its most frequent users could do to improve arbitrator diversity.

Does diversity in arbitrator appointments matter?

The first question that may be asked is whether a lack of diversity in arbitrator appointments even matters? If a CAS panel is made up of three eminent and experienced lawyers, does it matter that they are all white males? The answer is that while it may or may not make a difference to a given case, it does matter if such a lack of diversity persists for years and over thousands of cases.

First, as sports arbitration has grown, so too has its user-base, such that it is made up of men and women of a broad range of ethnicities. It is not unreasonable for that user-base to expect the arbitrator list, and the arbitrators actually appointed to resolve disputes, to be similarly diverse.

Such an expectation was the subject of litigation in 2018, after rapper Shawn Carter (aka Jay-Z) famously obtained an order staying an arbitration initiated by the Iconix Brand Group against him. Mr Carter argued that an arbitration clause that required him to submit to arbitration administered by the American Arbitration Association (“AAA”) was “void as against public policy” because the AAA did not have enough African-American arbitrators on its “large and complex cases” roster (indeed, from a list of more than 200 arbitrators, just three were identified by the AAA as African-American).

That state of affairs, according to Mr Carter, “deprives litigants of color of a meaningful opportunity to have their claims heard by a panel of arbitrators reflecting their backgrounds and life experience, and all but excludes the voices of diverse decision makers in the arbitration process.” Mr Carter added that “[s]uch exclusion risks an unconscious bias in decision-making”. Mr Carter eventually withdrew his request to halt the arbitration after, inter alia, (a) the AAA made available more African-American arbitrators for selection; and (b) the AAA agreed to consider Mr Carter’s own list of African-American candidates for addition to its “large and complex cases” roster.

Greater arbitrator diversity does not necessarily mean that disputes would be decided differently. However, an arbitrator’s life experiences will undoubtedly shape the lens through which they view the world. That becomes all the more relevant when one considers that many of the disputes at CAS require an arbitrator to consider a party’s life experiences.

For instance, in doping cases, arbitrators are often required to assess objective and subjective factors to determine an athlete’s degree of fault (and thus the sanction, if any, to be imposed). Those factors can include an athlete’s “personal circumstances”. However, an athlete’s personal circumstances – and whether those circumstances explain/mitigate the alleged wrong – may be less easily understood or accepted by an arbitrator whose life experiences are far removed from those of the athlete.

That is, of course, not to say that a white male arbitrator could not treat, for example, a black female athlete fairly. What it comes down to is the ability of arbitrators to place themselves in the shoes of an athlete. That may be more difficult for a panel of three middle-aged white male arbitrators to achieve in the case of a black female athlete, than perhaps might be the case for a more diverse panel.

Second, whilst experience is of course desirable, fresh perspectives and diversity of thought may lead to fairer and more rounded decisions. Numerous studies in recent years have indicated that heterogeneous groups generally outperform homogeneous ones.

Third, rightly or wrongly, CAS suffers from a perception in some quarters that it lacks independence and that CAS arbitrations are weighted against athletes. CAS was set up by the IOC and – whilst it has been administered by the International Council of Arbitration for Sport (“ICAS”) since 1994 – it currently derives much of its funding from Sports Governing Bodies (“SGBs”), such as the IOC and FIFA, which are frequent users of the CAS. In addition, it is not a secret that certain of its most frequent users, and the counsel that represent them, will repeatedly nominate from a small – and generally homogenous – group of arbitrators. Invariably – as is the case in the world of arbitration more generally – repeat nominations breed suspicion. That is particularly likely to be the case in the minds of one-time users of the CAS (e.g. athletes) who come up against regular users of the CAS such as SGBs. Add to that the fact that athletes are forced by the rules of SGBs to take disputes to arbitration, and one can perhaps understand why perceptions of unfairness and a lack of independence have occasionally arisen vis-à-vis the CAS.

One small but significant way in which that perception might be combatted would be if the frequent users of the CAS broadened the number and demographic profile of arbitrators that they nominate. Such an approach would lead to fewer repeat nominations, which would in turn assist in defusing at least some of the concerns created by the structural imbalances that already exist between the regular users of the CAS and those subject to their rules.

Thus, given those reasons, it is clear that diversity in arbitrator appointments at the CAS does matter. Ultimately, the CAS enjoys a privileged and high-profile position within the world of sport. By virtue of that single fact, the ICAS, the CAS and the SGBs whose rules mandate the use of CAS arbitration ought to lead by example and ensure greater diversity amongst appointed arbitrators. Doing so would likely lead to more rounded (and, in some cases, fairer) decisions, would modernise CAS’s image, and would afford the CAS greater legitimacy in the eyes of the broad communities that it is intended to serve.

Potential improvements

It is clear from the analysis in Part One that, whilst diversity in CAS arbitrator appointments has (for the most part) improved over the last 20 years, there is still a very long way to go. Accordingly, what can be done to improve matters, and to accelerate the pace of change?

As a preliminary matter, and in fairness to the CAS, it should be noted that, whilst more can always be done, the arbitrator list contains 370 arbitrators from 87 countries, covering six continents. Thus, as explained in Part One, the main problem lies with appointment practices rather than with the list – as exemplified by the fact that male arbitrators who have been appointed at least once receive, on average, almost twice as many appointments as the female arbitrators who have been appointed at least once. Fortunately, there are several potential solutions.

First, whilst the appointment practices are the main issue, and not the composition of the arbitrator list, it remains the case than an even broader, and more diverse, list of arbitrators would likely translate to greater panel diversity. Arbitrators may be added to the CAS arbitrator list following recommendations from CAS stakeholders, such as the SGBs. Given the importance of those recommendations, CAS stakeholders can obviously play their part by ensuring that their recommendations are as diverse as possible. In addition, if a stakeholder – for example, FIFA – were to successfully recommend several women for addition to the arbitrator list, then it ought also to nominate those women in CAS proceedings, not least since that stakeholder will presumably have satisfied itself as to the quality of the candidate before recommending them to be added to the list.

Second, while CAS could obviously do more to improve its record of appointing new arbitrators (as explored below), the parties also have a substantial role to play. Regrettably, many of the most regular users of the CAS (i.e. SGBs) limit themselves to a very small group of preferred arbitrators – who are experienced, but almost exclusively white and male. Therefore, in order to encourage the broadening of the pool, and thus to assist in improving diversity, the CAS could impose a limit on the number of times that a particular party can nominate a particular arbitrator (e.g. a maximum of three nominations within a three-year period). Whilst some may argue that this interferes with a key characteristic of arbitration – being the free will of the parties – that particular argument has less force in the context of the CAS, given that its most regular users (being SGBs) compel their members (e.g. athletes) to submit to CAS arbitration via a system of compulsory consent.

Third, and even if the CAS were to decline to impose such nomination limits, sports institutions could themselves pledge as a matter of internal policy to (a) limit their number of repeat nominations; and (b) ensure that their nominations are as diverse as reasonably possible. In this regard, it is notable that the five sports institutions that are most frequently involved in CAS proceedings have all extolled their commitment to diversity and inclusion. Whilst those commitments are typically generic, and not specific to arbitral proceedings, there is of course no reason why such policies should not extend to the nomination of arbitrators. Indeed, given that the CAS has become an integral element of international sport and given its elevated profile, failing to nominate demographically diverse arbitrators over a period of time may well make public commitments to diversity look rather hollow.

Choosing a familiar, tried-and-tested arbitrator – particularly in a high-stakes dispute – will always be tempting. Counsel will always fear the repercussions of nominating a new or unfamiliar arbitrator if the arbitration is ultimately lost. However, if SGBs commit to a policy of limiting repeat nominations and encouraging diversity then the issue will be taken out of the hands of counsel, who will not need to be as concerned about the “risk” of nominating someone new.

The current failings offer an opportunity for a progressive SGB to lead by example and to set a new paradigm. Should one of the major CAS users (i.e., an SGB) commit to diversifying their arbitrator nominations, it may well trigger a wider shift in attitude amongst other SGBs, such as to consign the current sorry state of affairs to history.

Fourth, CAS could do more to ensure that its arbitrator appointments are more diverse. For instance, and as regards the appeal cases studied, of the 1,464 presidents (all of which were appointed by the CAS) 3% were female, 3.9% were non-white and 0.7% were black. Thus, a commitment by the CAS to ensuring that president appointments are rotated so as to include a balance of female, black and other non-white arbitrators would significantly improve diversity. In this regard, it is notable that a similar system already exists elsewhere, as the National Sports Tribunal in Australia includes within its considerations for arbitrator appointments the “[g]ender balance of the panel” and “[r]otational selection of Members to support diversity”.

Fifth, CAS arbitrators themselves could do more to improve diversity in appointments. To explain, in ordinary cases to be heard by a panel, the two party-nominated arbitrators are expected to agree upon a panel president. Thus, those arbitrators should take diversity into account when selecting a president, and should be encouraged by the CAS to do so, perhaps via the circulation of a shortlist of potential candidates or by the production of a list of factors to be considered by the party-nominated arbitrators, which would include diversity considerations.

Importantly, all of the suggestions set out above could be implemented without the need for any compromise in arbitrator ‘quality’, as every arbitrator on the list has already been vetted by the CAS.

Sixth, the CAS could depart from its closed-list system, and thus allow the parties (and the CAS) to nominate whichever arbitrator they felt appropriate for a particular case. Notably, some arbitral institutions already operate in such a manner, such as arbitral procedures enacted under Rule K of The Football Association’s Rules, showing that such a system can function in a sports law context. Importantly, such a development would, of course, ensure that the ‘list’ of potential arbitrators was as diverse as possible. However, such a step would not alone ensure improved diversity in appointments since the predominant issue remains the (lack of) diversity of those arbitrators actually appointed to hear disputes. Accordingly, any such change would need to be implemented in conjunction with one or more of the other steps outlined above.

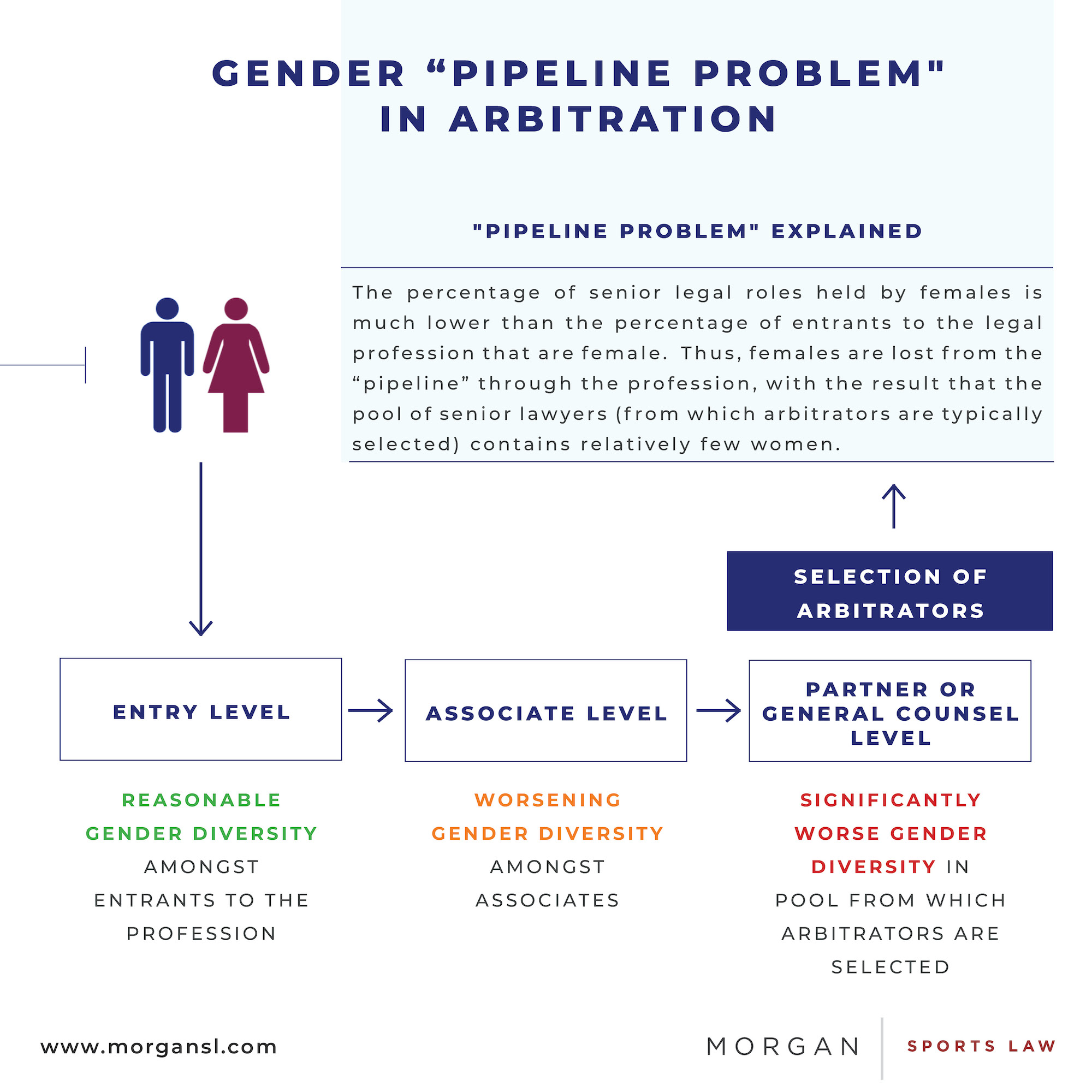

The “pipeline problem”?

It may be submitted that solutions specifically aimed at the CAS or its frequent users could not, alone, solve the arbitrator diversity issue, as women and ethnic minorities are underrepresented in the pool of lawyers from which potential arbitrators are drawn. This is the so-called “pipeline problem”, which is of course not unique to the diversity issue addressed in this series.

There is certainly room for improvement regarding the diversity of the arbitrator list (noting that just 12.5% of arbitrators on the CAS list are women, 24.5% are non-white (including black), and 4.4% are black). However, given that those percentages are far higher than the equivalent appointment percentages (as set out in Part One), it is apparent that the predominant issue has less to do with the “pipeline problem”, and more to do with the fact that these arbitrators (who are already on the arbitrator list) are not being appointed with the same frequency as their white male counterparts.

Nonetheless, the CAS, its stakeholders and the SGBs that require their members to submit to arbitration could be more active in attempting to combat the “pipeline problem” by providing assistance to women and ethnic minorities who are pursuing careers as professionals in sports law or arbitration. An example of such a scheme is the Higginbotham Fellows Program, set up by the AAA to assist “up and coming diverse alternative dispute resolution professionals who have historically not been included”. Such a scheme could be coupled with the work of other groups, such as Women In Sports Law, to assist in combatting the “pipeline problem”.

Conclusion

Of course, each of the suggestions set out above will have benefits, disadvantages and practical limitations. It may therefore be that combining some or all of the proposals (alongside any other reasonable suggestions) would be the best way to go.

However, regardless of the approach that is ultimately taken by the CAS and its most frequent users, it is clear that something needs to be done in order to ensure that CAS dispels the perception held in some quarters that it is an “old boys’ club”, so that it can better represent the diverse range of individuals it is intended to serve. The good news for CAS is that it would likely not take any substantial effort on its part to see measurable improvements in appointment diversity (noting that it alone is responsible for 45% of all appointments). If the SGBs – who are the most frequent users of the CAS and whose rules mandate CAS arbitration – would also commit to ensuring greater appointment diversity then the issue would largely disappear, and CAS could even become a model for other arbitral institutions as regards arbitrator diversity.

Further reading

For further reading regarding how arbitrator diversity might be improved in international arbitration please see here.

For further reading regarding how diversity positively impacts group performance; please see here.

Authored By

Mike Morgan

Managing Partner

Sam Comb

Science Analyst and Trainee Solicitor

Footnote

1. See, e.g., (1) CAS 2013/A/3327 & 3335 Cilic v. ITF at ¶¶ 69 - 95; (2) CAS OG AD 18/004 IIHF v. Jeglic at ¶¶ 61 - 67; and (3) Dr M. Viret and Dr E. Wisnosky, Still need proof sugar is bad for you? Cilic, glucose, “light” fault, and four months out (found at wadc-commentary.com/cilic/).

2. See, e.g., CAS 2017/A/5015 & 5110 FIS v. Johaug & NIF / Johaug v. NIF at ¶¶ 118 & 125.

3. See D. Pilawa, (2019) Sifting Through the Arbitrators for the Woman, the Minority, the Newcomer, Case W. Res. J. International Law 51(1): 395 - 429. See pp. 428 - 429: “….the majority of international arbitrators are white men from Western cultures. These arbitrators handle disputes from literally all over the world. We … are asking arbitrators to decide on large disputes based upon facts that possibly end up lost in cultural. translation. It is clear, then, that “[t]he determination of fact is probably the most culturally sensitive step [in the arbitral process], but the ability to correctly determine facts is perhaps the most ignored of all criteria for arbitrator selection.” Therefore, it is not the arbitrator’s culture that matters. It is more the arbitrator’s ability to understand the cultural significance of certain facts”.

4. E.g. (1) a study by Tufts University found that panels of white and black jurors performed better than all-white groups by a number of measures, and that the more diverse panels "deliberated longer, raised more facts about the case, and conducted broader and more wide-ranging deliberations, …. made fewer factual errors in discussing evidence and when errors did occur, those errors were more likely to be corrected during the discussion" (S. Sommers, (2006) On Racial Diversity and Group Decision Making: Identifying Multiple Effects of Racial Composition on Jury Deliberations, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 90(4): 597 - 612); (2) a McKinsey study of 1,000 companies, across 15 countries, found that diverse boards perform better than less diverse ones (S. Dixon-Fyle, et al. (2020) Diversity wins: How inclusion matters at https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/diversity-and-inclusion/diversity-wins-how-inclusion-matters); (3) a study by Credit Suisse found that businesses with women on the board outperformed those with male-only boards (see Credit Suisse press release of 31 August 2021 at https://www.credit-suisse.com/about-us-news/en/articles/media-releases/42035-201207.html); (4) researchers from Columbia, MIT, Northwestern, and other prestigious universities studied stock picking in ethnically homogeneous and diverse groups and found that “[m]ore diverse teams made more accurate pricing decisions, leading to fewer bubbles in the market. Their picks were 58% better than the picks of the homogeneous groups” (S. Levine, et al. (2014) Ethnic diversity deflates price bubbles, PNAS 111(52) https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1407301111); (5) a study that examined 1.5 million academic papers “found that papers written by diverse groups receive more citations and [have] higher impact factors than papers written by people from the same ethnic group.” (R. Freeman, et al. (2014) Collaborating with people like me: Ethnic co-authorship within the US http://www.nber.org/papers/w19905).

5. See the analysis in Part One, which noted that, of the 517 appointments made by the five most frequently appearing sports institutions, only 3.3% went to female arbitrators, only 6% went to non-white arbitrators, and only 0.2% went to black arbitrators (specifically, there was one appointment of a black arbitrator). Taking the appointments by the IOC as an (extreme) example, it appointed a total of 22 unique arbitrators in respect of 85 appointments, all of whom were white men.

6. See G. Deepak, (2016) Compulsory consent in Sports Arbitration: Essential or Auxillary, Kluwer Arbitration Blog (http://arbitrationblog.kluwerarbitration.com/2016/04/12/compulsory-consent-in-sports-arbitration-essential-or-auxiliary/) which states: “The issue is further complicated by the nature of CAS and the method of appointment adopted for its panel of arbitrators, which seems to be heavily biased in favour of Sports Governing Bodies, at least from the perspective of any athlete.”

7. Note that the body responsible for compiling and updating the list of arbitrators eligible for appointment to CAS cases is the ICAS - a council of 20 members (primarily appointed by SGBs) who are responsible for the administration of the CAS.

8. Notably, article S16 of the ICAS Statutes provides that “[w]hen appointing arbitrators and mediators, the ICAS shall consider continental representation and the different juridical cultures”. The existence of article S16 may in part explain why the arbitrator list is relatively diverse compared to the profile of the arbitrators actually appointed to hear disputes.

9. See S14 of the ICAS Statutes: The ICAS shall appoint personalities to the list of CAS arbitrators with appropriate legal training, recognized competence with regard to sports law and/or international arbitration, a good knowledge of sport in general and a good command of at least one CAS working language, whose names and qualifications are brought to the attention of ICAS, including by the IOC, the IFs, the NOCs and by the athletes' commissions of the IOC, IFs and NOCs. ICAS may identify the arbitrators with a specific expertise to deal with certain types of disputes.

10. See fn 5.

11. See for example, D. Pilawa (2019) Sifting Through the Arbitrators for the Woman, the Minority, the Newcomer, Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law 51(1) 395 - 435 (https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2549&context=jil) which notes that some parties view efforts to control arbitrator selection processes “as infringing upon the sacrosanct freedom that international arbitration promises”.

12. Namely FIFA, WADA, the IOC, the UCI, and UEFA, as identified in research by Professor Johan Lindholm (J. Lindholm, (2019) CAS from the Litigants’ Perspective. In: J. Lindholm, (Ed.) The Court of Arbitration for Sport and Its Jurisprudence, T.M.C. Asser Press, 1. 287 - 312).

13. For examples of those commitments, see: (1) the IOC President Thomas Bach’s manifesto which is entitled “Unity in Diversity” and makes clear the importance of diversity to the Olympic movement (https://stillmed.olympic.org/Documents/IOC_President/Manifesto_Thomas_Bach-eng.pdf). “Unity in Diversity” is also one of the “Working Principles” listed on the IOC Principles webpage (see https://olympics.com/ioc/principles); (2) WADA’s Strategic Plan 2020-2024, which states that it will “[s]upport diversity and inclusion in representation of stakeholders and external experts across all WADA decision-making bodies, Standing Committees and Expert Groups” (https://www.wada-ama.org/sites/default/files/resources/files/wada_strategyplan_20202024.pdf); (3) UEFA’s Football and Social Responsibility webpage, which states that “UEFA encourages an inclusive culture and practices in football. It endorses the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of each individual, while embracing differences such as ethnicity, age, gender…” (https://www.uefa.com/insideuefa/social-responsibility/overview/); (4) the UCI’s Diversity and Inclusion webpage which states that “[d]iversity and its promotion is an area where [the UCI] have sought to make progress” and reports that the UCI “will develop new policies and recommendations to promote diversity, equality and inclusion” (https://www.uci.org/diversity-and-inclusion/3o8vLG6wbzkWlVQz1ocnXl); and (5) numerous FIFA policy documents on diversity and inclusion – such as the Good Practice Guide on Diversity and Anti-Discrimination (https://digitalhub.fifa.com/m/6363f7dc616ff877/original/wg4ub76pezwcnxsaoj98-pdf.pdf). In addition, FIFA’s Chief Education and Social Responsibility Officer has stated that “[d]iversity and inclusion is a hugely important topic for FIFA” (see https://www.sports-insight.co.uk/associate-news/diversity-and-inclusion-is-a-hugely-important-topic-for-fifa-says-joyce-coo), and FIFA’s Secretary General has said that “There is definitely room for improvement in the football industry to become more diverse at all levels, […] [w]e aim to lead by example - last year we launched a women's leadership programme. […] in its reforms, FIFA has also introduced regulations and requirements to ensure a more diverse representation at the executive level” (see https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-37400409).

14. See article R40.2 of the CAS Code of Sports-related Arbitration which provides that “[t]he two arbitrators so appointed shall select the President of the Panel by mutual agreement within a time limit set by the CAS Court Office.”

15. Given the specialist nature of the sports law disputes, there are arguments (many of which are entirely legitimate) as to why a closed list of (specialist) arbitrators is preferable. That is a topic in itself and is beyond the scope of this article. For further reading on the advantages and disadvantages of closed lists in arbitration, see: (1) the ICLGs’ Closed list arbitrator appointments: A case study (https://iclg.com/cdr/arbitration-and-adr/7818-closed-list-arbitrator-appointments-a-case-study). (2) A. Santens, (2011) The Move Away from Closed-List Arbitrator Appointments: Happy Ending or a Trend to Be Reversed?, Kluwer Arbitration Blog (http://arbitrationblog.kluwerarbitration.com/2011/06/28/the-move-away-from-closed-list-arbitrator-appointments-happy-ending-or-a-trend-to-be-reversed/).

16. The “pipeline problem” is a shorthand term used to explain the situation whereby relatively few minority individuals occupy the senior legal roles from which arbitrators are typically selected. Commentators talk of “leaks” of minority individuals from the profession at each stage of the career “pipeline” – as there is typically greater representation of minorities at junior levels than at senior levels. For further reading on the “pipeline problem”, see: (1) Codio’s “taking a Closer Look at the “Pipeline Problem” (https://www.codio.com/blog/taking-a-closer-look-at-the-pipeline-problem); and (2) A. Rhodes Vivous’ Keynote Speech: Promoting Gender Diversity in Arbitration in Africa, Women in Arbitration Conference, Nairobi, 23 March 2018 (https://drvlawplace.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/ADEDOYIN-RHODES-VIVOUR-KEYNOTE-SPEECH.pdf).